Posttribulation rapture

| Christian eschatology |

|---|

| Christianity portal |

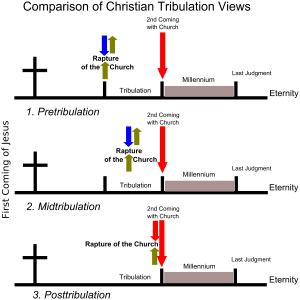

The posttribulation rapture doctrine is the belief in a combined resurrection and rapture, or gathering of the saints, that occurs after the Great Tribulation but before the millennial reign of Christ.[1] It differs from other rapture views such as pretribulation, midtribulation, and prewrath.

There are four variants of this view: classic, semiclassic, futurist, and dispensational. It may be a premillennial,[2] postmillennial, or amillennial view.[3]

Doctrine

[edit]The posttribulation rapture doctrine is an eschatological concept which relates the rapture of the Church, which refers to Christ gathering the saints prior to his return, to the tribulation, which refers to a time of trouble and suffering, and Christ's Second Coming.[4]

The definition is one of timing, with posttribulationism placing the timing of the rapture at the end of the tribulation period. The rapture of the saints and the Second Coming are a single event.[4] This is in contrast with the two-stage pretribulation rapture view that places the rapture prior to the tribulation period followed by the Second Coming.[4] Posttribulationists point out that a two-stage return is never mentioned in the Bible.[5]

Central to the concept of a rapture of the Church is 1 Thessalonians 4:15–17. Posttribulationists believe that, unlike the idea of a secret rapture in the pretribulation view, this text describes a visible, public appearing of Christ. They also use the comparative text in Matthew 24:30–31 to support this idea.[4] A comparison of these two passages shows they both mention the same individuals and events in the same order.[6]

| Matthew 24:30-31 | 1 Thessalonians 4:15-17 |

|---|---|

| They shall see the Son of man coming. | The Lord himself shall descend from heaven. |

| His angels, with a great voice. | With the voice of the archangel. |

| With a great trumpet. | With the trumpet of God. |

| They shall gather together his elect. | Caught up together with them. |

| In the clouds of heaven. | In the clouds to meet the Lord. |

The use of the word meet in 1 Thessalonians 4:17 refers to the customary practice of a delegation going outside the city to meet an arriving dignitary and providing an escort back to the city. This term is used in two other places in scripture where it has the same meaning. Once in Matthew 25:6 when the wise virgins meet the bridegroom to escort him to the wedding feast, and in Acts 28:15 when the Christians go out to meet Paul and escort him into Rome. In the posttribulational rapture view, 1 Thessalonians 4:17 is describing all believers forming a single welcoming party and escorting Jesus to earth for his millennial reign.[7]

Posttribulationist Robert Gundry notes that phrasing in the texts suggests rapture after the tribulation, and not before as in the pretribulational view. He further points out that 2 Thessalonians 1:5-10 indicates not a pretribulational rapture where Christians would be removed from suffering, but that the relief of Christians from their persecution would take place at the revealing of Jesus Christ with fire and judgment, which describes the coming of Christ at the end of the tribulation.[8]

There is a difference between God's wrath and the tribulation in the posttribulation view. Christians do not experience the wrath of God according to 1 Thessalonians 1:9–10 and 1 Thessalonians 5:9, but they are not promised immunity from persecution by God's enemies. In the Great Tribulation, God pours out his wrath on the wicked, but persecution is the wrath of Satan against God's people. Although believers may be persecuted unto death, their relationship to God remains protected.[7]

This concept is exemplified by Revelation 3:10, in which Jesus promises the Philadelphian church, "I will keep you from the hour of trial that is going to come upon the whole world to test those who live on the earth."[9] This may be the most debated text when considering timing of the rapture.[10] The pretribulation rapture view considers the phrase "keep from" to mean a physical removal while the posttribulation view interprets this as "protected through".[11] However, the verse says the testing is for "those who dwell on the earth". Postttribulationists take this to be characterizing a selective nature of God's wrath and that it refers only to unbelievers.[12] Posttribulationists compare the promise in Revelation 3:10 to Jesus's prayer in John 17:15 where he uses the same verb (in the Greek), "My prayer is not that you take them out of the world but that you protect them from the evil one".[13]

Posttribulationism may not take a literal view of the millennium, or Christ's reign on earth following the Second Coming. While pretribulationists tend to speak of the millennium as a literal 1,000 year reign, it is not necessarily so with posttribulationism.[14]

Variations

[edit]Classic posttribulationism

[edit]In this view, the Church has always been in the Great Tribulation, which is already been fulfilled. It is a major view that can be traced to the early church. The tribulation is spiritualized, or non-literal.[15] The tribulation precedes the Second Coming, after which there will be a literal Millennium (1,000 year reign of Christ on earth).[16] The concept of a rapture of the church precedes the Second Coming.[17] The view is a form of historicism.[18] In a historicist view, Daniel's 70th week is already fulfilled.[19]

A modern proponent of this view is J. Barton Payne, who published his view in The Imminent Appearing of Christ.[18] Payne drew support for his ideas from the First Epistle of Clement, the Epistle of Barnabas, the Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians, and the Epistle of Ignatius to Polycarp.[20]

Semiclassic posttribulationism

[edit]Unlike classic posttribulationism which sees the tribulation extending from the beginning of the church, this view considers the Great Tribulation to be a contemporary event. In this view, there are unfulfilled prophecies that precede the Second Coming, and therefore the Second Coming cannot be imminent.[21]

Semiclassic posttribulationism has varying views on the extent of the tribulation period. Some view it to be the entire span of human history and others see it as the church age. There are others that see the "Great Tribulation" as separate and distinct from the tribulation itself, believing that the tribulation extends through church history, but the Great Tribulation has yet to occur.[22]

In some views, the church and Israel are members of the same spiritual community, while in others, the church is separate from Israel.[22]

John Walvoord considers this to be the view held by the majority of contemporary posttribulationists.[21]

Futurist posttribulationism

[edit]While the classic and semiclassic views see some form of tribulation extending throughout the church age, the futurist view sees the concept of the tribulation as a future event that has not yet happened.[23]

One of the leaders of this view is George Eldon Ladd who published it in The Blessed Hope.[23]

Dispensational posttribulationism

[edit]The dispensational posttribulational view attempts to combine dispensationalism with posttribulationism.[24] A dispensational posttribulational view operates on the assumption that Daniel's 70th week is yet unfulfilled.[25]

This view began with Robert H. Gundry's work, The Church and the Tribulation.[24] His view separates Israel from the church, a distinction found in dispensationalism.[26] Gundry states that the redeemed multitude that comes out of the great tribulation constitutes the last generation of the Church.[27]

Gundry states that the Ante-Nicene Fathers favored a premillennial posttribulational eschatology.[28] He lists Clement of Alexandria and Origen as the only early church writers who did not favor a posttribulational view.[29] He further suggests that the earliness of posttribulationsism favors apostolicity and that the late origin of amillennialism and postmillennialism indicates human invention.[30]

Comparison with other views

[edit]

Pretribulationism

[edit]Pretribulationism is a view within premillennialism that the return of Christ is a two-stage event beginning with the rapture. This occurs just prior to the tribulation, a seven-year period of God's wrath on earth, the end of which will culminate with Christ's Second Coming to set up an earthly kingdom.[31] This view was popularized by John N. Darby.[32]

A key issue of disagreement between pretribulationism and posttribulationism is whether the church will experience persecution under Antichrist. Pretribulationism teaches that the church has been raptured before the tribulation beings, and is thus protected from persecttion. Posttribulationism believes that the rapture is an event at the end of the tribulation, and that the church will experience persecution during that time.[33]

Also contrasted with posttribulationism, pretribulationism views the parousia, or Christ's appearing, as a two-stage event; first in the rapture and then with his return to earth in the Second Coming. This is a single event in posttribulationism, as they both happen at the same time.[31]

Pretribulationism emerged as a new doctrine following a resurgence in postmillennialism in the early 1800s.[34] After competing with posttribulationism for dominance during the late 1800s, and by the 1920s, it had become the most widely accepted eschatological doctrine in the United States.[34] It is generally taught in evangelical churches to the exclusion of all other views. It is usually associated with dispensationalism.[34]

Midtribulationism

[edit]Midtribulationism is a view that the church will be present on earth during the first half of Daniel's seventieth week (three and one-half years) and will experience tribulation.[35] The church will be raptured halfway through the seventieth week and avoid God's outpouring of wrath.[36] Similar to posttribulationism, this view makes a distinction between tribulation and wrath.[35] It is considered to be a minority view.[34]

In The Blessed Hope, George Ladd suggests this view is a variant of pretribulationism.[37] In The Church and the Tribulation, Robert Gundry suggests it is an unstable view that may be in line with pretribulationism or posttribulationism, depending on the other arguments assumed.[38] More recently, this view has been supplanted by the prewrath rapture view.[33]

Prewrath

[edit]The prewrath rapture position is based on two premises. First, that the church will enter the last half of Daniel's seventieth week (the last half of the Great Tribulation), and second, that between the rapture of the church and Christ's return there will be a period of divine wrath upon the earth.[39] This position differs from midtribulationism in the rapture is not associated with the middle o f Daniel's seventieth week, but with the outpouring of God's wrath during the last half of the week.[31]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Archer et al. 1996, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Ladd 1956, p. 10.

- ^ Walvoord 1979, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Hays, Duvall & Pate 2007, p. 337.

- ^ Hoekema 1979, p. 165.

- ^ Baxter 1986, p. 218.

- ^ a b Hays, Duvall & Pate 2007, p. 338.

- ^ Gundry 1997, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Blaising, Hultberg & Moo 2010, p. 62; Hays, Duvall & Pate 2007, p. 338.

- ^ Gundry 1973, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Blaising, Hultberg & Moo 2010, p. 63.

- ^ Archer et al. 1996, p. 97.

- ^ Hays, Duvall & Pate 2007, p. 339.

- ^ Erickson 1977, p. 161.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 51.

- ^ Walvoord 1979, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Walvoord 1979, p. 137.

- ^ a b Gundry 1973, p. 193.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 189.

- ^ Walvoord 1979, p. 136.

- ^ a b Walvoord 1979, p. 139.

- ^ a b Walvoord 1979, p. 140.

- ^ a b Walvoord 1979, p. 142.

- ^ a b Walvoord 1979, p. 143.

- ^ Gundry 1973, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Walvoord 1979, p. 144.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 80.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 178.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 179.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Blaising, Hultberg & Moo 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Archer et al. 1996, p. 12.

- ^ a b Blaising, Hultberg & Moo 2010, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Blaising, Hultberg & Moo 2010, p. 16.

- ^ a b Hays, Duvall & Pate 2007, p. 285.

- ^ Hays, Duvall & Pate 2007, p. 286.

- ^ Ladd 1956, p. 12.

- ^ Gundry 1973, p. 200.

- ^ Blaising, Hultberg & Moo 2010, p. 109.

Sources

[edit]- Archer, Gleason L.; Feinberg, Paul D.; Moo, Douglas J.; Reiter, Richard R. (1996). Archer, Gleason Leonard (ed.). Three Views on the Rapture: Pre, Mid, or Posttribulation?. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-21298-0.

- Baxter, J. Sidlow (1986-12-26). Baxter's Explore the Book. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-20620-0.

- Erickson, Millard J. (1977). Contemporary Options in Eschatology: A Study of the Millennium. Baker Books. ISBN 978-0-8010-3262-2.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Hultberg, Alan; Moo, Douglas J. (2010). Hultberg, Alan (ed.). Three Views on the Rapture: Pretribulation, Prewrath, Or Posttribulation. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-27720-0.

- Gundry, Robert H. (1997). First the Antichrist. Baker Books. ISBN 978-0-8010-5764-9.

- Gundry, Robert H. (1973). The Church and the Tribulation: A Biblical Examination of Posttribulationism. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 0-310-25401-9.

- Hays, J. Daniel; Duvall, J. Scott; Pate, C. Marvin (2007). Dictionary of Biblical Prophecy and End Times. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-25663-2.

- Hoekema, Anthony A. (1979). The Bible and the Future. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3516-1.

- Ladd, George Eldon (1956). The Blessed Hope: A Biblical Study of the Second Advent and the Rapture. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-1111-0.

- Walvoord, John F. (1979). The Rapture Question. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-310-34151-2.