Plasmoid

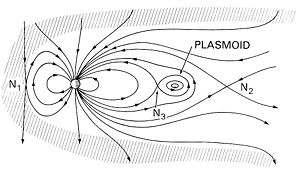

A plasmoid is a coherent structure of plasma and magnetic fields. Plasmoids have been proposed to explain natural phenomena such as ball lightning,[1][2] magnetic bubbles in the magnetosphere,[3] and objects in cometary tails,[4] in the solar wind,[5][6] solar atmosphere,[7] and in the heliospheric current sheet. Plasmoids produced in the laboratory include the compact toroids (similar to a vortex ring in low temperature fluid dynamics or hydrodynamics) field-reversed configurations, spheromaks, and filamentary variants in dense plasma focuses.

The word plasmoid was coined in 1956 by Winston H. Bostick (1916–1991) to mean a "plasma-magnetic entity":[8]

The plasma is emitted not as an amorphous blob, but in the form of a torus. We shall take the liberty of calling this toroidal structure a plasmoid, a word which means plasma-magnetic entity. The word plasmoid will be employed as a generic term for all plasma-magnetic entities.

— Winston H. Bostick

Plasmoid characteristics

[edit]Bostick researched the basic traits, and many details, of plasmoids.

Plasmoids appear to be plasma cylinders elongated in the direction of the magnetic field. Plasmoids possess a measurable magnetic moment, a measurable translational speed, a transverse electric field, and a measurable size. Plasmoids can interact with each other, seemingly by reflecting off one another. Their orbits can also be made to curve toward one another. Plasmoids can be made to spiral to a stop if projected into a gas at about 10−3 mm Hg pressure. Plasmoids can also be made to smash each other into fragments. There is some scant evidence to support the hypothesis that they undergo fission and possess spin.[8]

— Winston H. Bostick

A plasmoid has an internal pressure stemming from both the gas pressure of the plasma and the magnetic pressure of the field. To maintain an approximately static plasmoid radius, this pressure must be balanced by an external confining pressure. In a field-free vacuum, a plasmoid expands and dissipates rapidly.

Plasmoids have been formed in discharges with local magnetic field strengths on the order of 16,000 Tesla.[9]

Astronomic applications

[edit]Bostick went on to apply his theory of plasmoids to astrophysics phenomena. His 1958 paper,[10] applied plasma similarity transformations to pairs of plasmoids fired from a plasma gun (dense plasma focus device) that interact in such a way as to simulate an early model of galaxy formation.[11][12]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Silberg, Paul A. (November 1962). "Ball lightning and plasmoids". Journal of Geophysical Research. 67 (12): 4941–4942. Bibcode:1962JGR....67.4941S. doi:10.1029/JZ067i012p04941.

- ^ Friday, DM; Broughton, PB; Lee, TA; Schutz, GA; Betz, JN; Lindsay, CM (3 October 2013). "Further insight into the nature of ball-lightning-like atmospheric pressure plasmoids". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 117 (39): 9931–40. Bibcode:2013JPCA..117.9931F. doi:10.1021/jp400001y. PMID 23767686.

- ^ Hones, E. W., Jr., "The magnetotail – Its generation and dissipation", (1976) Physics of solar planetary environments; Proceedings of the International Symposium on Solar-Terrestrial Physics, Boulder, Colo., June 7–18, 1976. Volume 2.

- ^ Roosen, R. G.; Brandt, J. C., "Possible Detection of Colliding Plasmoids in the Tail of Comet Kohoutek" (1976), Study of Comets, Proceedings of IAU Colloq. 25, held in Greenbelt, MD, 28 October – 1 November 1974. Edited by B. D. Donn, M. Mumma, W. Jackson, M. A'Hearn, and R. Harrington. National Aeronautics and Space Administration SP 393, 1976., p.378

- ^ Lemaire, J.; Roth, M. (26 March 1981). "Differences between solar wind plasmoids and ideal magnetohydrodynamic filaments". Planetary and Space Science. 29 (8): 843–849. Bibcode:1981P&SS...29..843L. doi:10.1016/0032-0633(81)90075-1.

- ^ Wang, S.; Lee, L. C.; Wei, C. Q.; Akasofu, S.-I., A mechanism for the formation of plasmoids and kink waves in the heliospheric current sheet (1988) Solar Physics (ISSN 0038-0938), vol. 117, no. 1, 1988, p. 157–169.

- ^ Cargill, P. J.; Pneuman, G. W. (August 15, 1986). "The energy balance of plasmoids in the solar atmosphere". Astrophysical Journal, Part 1. 307: 820–825. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b Bostick, Winston H (1956). "Experimental Study of Ionized Matter Projected across a Magnetic Field". Physical Review. 104 (2): 292–299. Bibcode:1956PhRv..104..292B. doi:10.1103/physrev.104.292.

- ^ "Theoretical Analysis of the Electron Spiral Toroid Concept" (PDF).

- ^ Bostick, Winston H., "Possible Hydromagnetic Simulation of Cosmical Phenomena in the Laboratory" (1958) Cosmical Gas Dynamics, Proceedings from IAU Symposium no. 8. Edited by Johannes Martinus Burgers and Richard Nelson Thomas. International Astronomical Union. Symposium no. 8, p. 1090

- ^ W. L. Laurence, "Physicist creates universe in a test tube," New York Times, p. 1, December 12, 1956.

- ^ Bostick, W. H., "What laboratory-produced plasma structures can contribute to the understanding of cosmic structures both large and small" (1986) IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science (ISSN 0093-3813), vol. PS-14, December 1986, p. 703–717.

References

[edit]- Bostick, W. H., "Experimental Study of Plasmoids", Electromagnetic Phenomena in Cosmical Physics, Proceedings from IAU Symposium no. 6. Edited by Bo Lehnert. International Astronomical Union. Symposium no. 6, Cambridge University Press, p. 87.