LGBTQ rights in Armenia

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (August 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

LGBTQ rights in Armenia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Status | Legal since 2003[1] |

| Military | LGBT people are not allowed to serve openly |

| Discrimination protections | No law prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned |

| Adoption | Same-sex couples are not allowed to adopt |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Armenia face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents, due in part to the lack of laws prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity and in part to prevailing negative attitudes about LGBT persons throughout society.

Homosexuality has been legal in Armenia since 2003.[1] However, even though it has been decriminalized, the situation of local lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) citizens has not changed substantially. Many LGBT Armenians fear being socially outcast by their friends and families, causing them to keep their sexual orientation or gender identity secret, except to a few family members and friends.[2]

Homosexuality remains a taboo topic in many parts of Armenian society. In a 2012 study, 55% of correspondents in Armenian stated that they would cease their relationship with a friend or relative if they were to come out as gay. Furthermore, this study found that 70% of Armenians find LGBT people to be "strange".[3] There is, moreover, no legal protection for LGBT persons whose human rights are frequently violated.[4][5] In 2024, ILGA-Europe ranked Armenia 46th out of 49 European countries for the protection of LGBT rights, marking progress compared to the previous year.[6]

Many LGBT individuals report fearing violence in their workplace or from their family, leading to underreporting of human rights violations and criminal offences.[7] As a result, reported incidents of discrimination, harassment, or hate crimes likely underestimate their true prevalence.

In 2011, Armenia signed the "joint statement on ending acts of violence and related human rights violations based on sexual orientation and gender identity" at the United Nations, condemning violence and discrimination against LGBT people.[8]

Legality of same-sex sexual activity

[edit]Between 1920 and 1991, Armenia was part of the Soviet Union. Until 2003, the legislation of Armenia followed the corresponding Section 121 from the former Soviet Union Penal Code, which specifically criminalized anal intercourse between men. Lesbian and non-penetrative gay sex between consenting adults was not explicitly mentioned in the law as being a criminal offence.

The specific article of the Penal Code was 116, dating back to 1936, and the maximum penalty was five years' imprisonment.

The abolition of the anti-gay law along with the death penalty was among Armenia's pre-accession conditions to the Council of Europe in 2001. In December 2002, the Azgayin Zhoghov (National Assembly) approved the new penal code in which the anti-gay article was removed. On 1 August 2003, President of Armenia Robert Kocharyan ratified it, thus making Armenia the last Council of Europe member state where same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized.

There were seven prosecutions in 1996 and four in 1997 under the law (according to Amnesty International), and four in 1999 (according to the Legal Affairs and Human Rights Committee of the Council of Europe).

In 2001, local human rights NGO "Helsinki Association" published via its website the story of a 20-year-old.[9][10] In 1999, the young man was sentenced to three months of imprisonment for having sex with another man. He was the last to be condemned under Article 116. In his testimony, he denounced prison guard abuse and mistreatment but also the corrupt judge who shortened his sentence for a $US1,000 bribe. The mediatization or publicizing of his case signaled the first gay "coming out" in Armenia.

The age of consent is 16, regardless of gender and sexual orientation.

Recognition of same-sex relationships

[edit]

Same-sex marriage and civil unions are not legal in Armenia and the Constitution limits marriage to opposite-sex couples.[11][12]

In late 2017, Father Vazken Movsesian of the Armenian Apostolic Church, a high-ranking member of the clergy, expressed his personal support for same-sex marriage, becoming one of the most high-profile supporters of same-sex marriage in Armenia. In an interview with Equality Armenia, Movsesian likened the historic persecution of Armenians by Turkey to the persecution faced by LGBT people. "We've been persecuted because we were not accepted, because we were different. As an Armenian Christian, how can I possibly close my eyes to what's going on in the world? And it's not just in Armenia, just everywhere, this intolerance", he said.[importance?][13][14] Other supporters include organisation Equality Armenia, whose goal is "achieving marriage equality in Armenia".[importance?][15]

In November 2018, the Armenian Government rejected a bill proposed by MP Tigran Urikhanyan to introduce further prohibitions on same-sex marriage.[16]

On 26 August 2019, the Minister of Justice, Rustam Badasyan, stated that Armenia does not recognize same-sex marriage.[17]

Discrimination protections

[edit]Although Armenia was among the first states in the region to endorse the UN declaration on sexual orientation and gender identity in December 2008, as of 2024, there is no legislation protecting LGBT individuals from discrimination. A 2011 survey revealed that 50% of Armenians would "walk away indifferently" if they witnessed violence against an LGBT person, underscoring the deeply ingrained cultural opposition to homosexuality.[3]

In a 2024 statement on anti-discrimination legislation in Armenia, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe appealed to the Armenian Government and Parliament to ensure the protection of the rights of LGBTI people, proposing the following recommendations:[18]

- the explicit inclusion of sexual orientation, gender identity and/or expression and sex characteristics, as protection grounds;

- the inclusion of a provision, allowing human rights organizations to bring claims related to the protection of public interest;

- the establishment of an independent equality body, empowered by the Parliament, to oversee and address discrimination cases.

On 30 January 2024, the administrative court of Yerevan ruled in favor of granting Salman Mukayev, a Russian citizen from Chechnya, asylum and refugee status. Fearing persecution for homosexuality in Chechnya, Mukayev applied for asylum in Armenia. The courts decision was based on concerns over the repressive treatment of the LGBT community in both Chechnya and Russia.[19]

ILGA-Europe conducts activities related to advancing LGBT rights in Armenia through seven NGO's and civil societies based in Armenia.[20]

Military service

[edit]According to the Helsinki Committee of Armenia, in 2004, an internal defence ministry decree effectively bans gay men from serving in the armed forces. In practice, gays are marked as "mentally ill" and sent to a psychiatrist.[21]

Living conditions

[edit]Violence and homophobia/transphobia

[edit]In the fall of 2004, Armen Avetisyan, founder of the extreme right group Armenian Aryan Union (AAU), announced that some top Armenian officials were gay. Various parliament members initiated heated debates which were broadcast on public TV, and asserted that any member found to be gay should resign, an opinion also shared by Presidential Advisor for National Security Garnik Isagulyan.[22]

In May 2012, suspected "Neo-Nazis" launched two arson attacks at a lesbian-owned pub in Armenia's capital, Yerevan. Armenian News reported that in the second attack on 15 May, a group of young men arrived at the gay DIY Rock Pub around 6pm, where they burned the bar's "No to Fascism" poster and drew the Nazi Swastika on the walls. This followed another attack on 8 May in which a petrol bomb was thrown through the Rock Pub's window.[23]

In May 2018, while in Armenia on a humanitarian mission, Elton John was subjected to homophobic slurs and eggs were hurled at him. The suspect was later released by the police.[24][25]

In August 2018, nine LGBT activists were violently attacked by a mob at a private home in the town of Shurnukh, sending two of them to hospital for serious injuries. The violent attack received widespread media coverage,[26] and was condemned by human rights groups and the U.S. embassy.[27][28] The attackers were later released by the police.[29]

Since the 2018 Velvet Revolution, the new pro-western regime has made some inroads. with Pink Armenia, but still lacking in protections in the west.[30]

In April 2023, police raided Poligraf, a prominent nightclub in Yerevan known as a safe space for Armenia's LGBTQ+ community, detaining over forty individuals. Pink Armenia has condemned the incident, with chairperson Lilit Avetisyan stating, "They laid all those present on the ground, used violence, took everyone to the police department, and started mocking them, mainly based on their clothing and sexual orientation."[31]

On 21 August 2023, at a candlelight vigil for a murdered trans woman named Adriana, organized by Right Side NGO in Komitas Park in Yerevan, more than 100 LGBTQ+ activists gathered, along with Adriana's family, the Dutch ambassador to Armenia and a representative from the British embassy. The vigil was disrupted by a group of agitators who threw eggs, bottles, and stones at the mourners. Police officers, who had gathered in the park in preparation for the vigil, did not intervene.[32]

Activism

[edit]

Following the abolition of the anti-gay law, some sporadic signs of an emerging LGBT rights movement were observed in Armenia. In October 2003, a group of 15 LGBT people gathered in Yerevan to set up an organization which was initially baptised GLAG (Gay and Lesbian Armenian Group). But after several meetings, the participants failed to achieve their goal.

In 1998, the Armenian Gay and Lesbian Association of New York was founded to support LGBT diasporan Armenians.[33] A similar group was also established in France.

In 2007, Pink Armenia,[34] another NGO, emerged to promote public awareness on HIV and other STI (sexually transmitted infections) prevention but also to fight discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Pink conducts research on the status of LGBT people in Armenia, while working with other NGOs to combat homophobia.

Other LGBT groups include the GALAS LGBTQ+ Armenian Society, the Armenia Rainbow Initiative, and Equality Armenia, which is based in Los Angeles, United States.[35]

On 5 April 2019, transgender MP Lilit Martirosyan, took the floor at the National Assembly of Armenia and talked about the hopes for a better and more secure future for the LGBT community in Armenia. Her speech marked the first time in the history of Armenia that a transgender person had spoken in the National Assembly.[36] She described herself as "the embodiment of a tortured, raped, kidnapped, physically assaulted, burnt, murdered, robbed and unemployed Armenian transgender." Her speech faced a lot of backlash, specifically MP Naira Zohrabyan who quit the National Assembly during the speech and threats from MP Vartan Ghukasian to have her burnt alive.[37] In February 2020, a member of an Armenian nationalist party tried to "clean up" Armenia's National Assembly. "Since the lectern of the National Assembly has been desecrated," Sona Aghekyan announced, "I'm going to burn incense here." Aghekyan was referring to transgender activist Lilit Martirosyan, who made a brief speech in parliament from the same lectern in 2019.[38]

Freedom of speech and expression

[edit]In 2013, the Armenian police proposed a bill outlawing "non-traditional sexual relationships" and the promotion of LGBT "propaganda" to youth in a law similar to the Russian anti-gay law.[39] Ashot Aharonian, a police spokesperson, stated that the bill was proposed due to the public's fear of the spreading of homosexuality. However, NGOs including Pink Armenia claimed that this was an attempt to distract the public from various sociopolitical issues within the country. The bill ultimately failed to pass.[40]

In November 2018, a Christian LGBT group had to cancel several forums and events it had planned due to "constant threats" and "organized intimidation" from political and religious leaders, as well as a "lack of sufficient readiness" from the police force to protect them.[41]

Iravunk newspaper incident

[edit]On 17 May 2014, the Iravunk newspaper published an article with a list of dozens of people's Facebook accounts from the Armenian LGBT community, calling them "zombies" and accused them of serving the interest of the international homosexual lobby.[42] The newspaper was sued and taken before the Armenian Court of Appeals, where the judges found that the newspaper did not offend anybody and ordered the plaintiffs to pay 50,000 dram (US$120) as compensation to the newspaper and its editor, Hovhannes Galajyan.[43]

Human rights reports

[edit]2017 United States Department of State report

[edit]In 2017, the United States Department of State reported the following, concerning the status of LGBT rights in Armenia:

- "The most significant human rights issues included: torture; harsh and life threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; lack of judicial independence; failure to provide fair trials; violence against journalists; interference in freedom of the media, using government legal authority to penalize critical content; physical interference by security forces with freedom of assembly; restrictions on political participation; systemic government corruption; failure to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons from violence; and worst forms of child labor, which the government made minimal efforts to eliminate."[44]

- Prison and Detention Center Conditions

"The Prison Monitoring Group noted that homosexual males, those associating with them, and inmates convicted of crimes such as rape, were segregated from other inmates and forced to perform humiliating jobs and provide sexual services."[44] - Academic Freedom and Cultural Events

"In July organizers of the Golden Apricot International Film Festival canceled the screening of two LGBTI-themed films after negative public reaction (see section 6, Acts of Violence, Discrimination, and Other Abuses Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity)."[44] - Acts of Violence, Discrimination, and Other Abuses Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

"Antidiscrimination laws do not apply to sexual orientation or gender identity. There were no hate crime laws or other criminal judicial mechanisms to aid in the prosecution of crimes against members of the LGBTI community. Societal discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity negatively affected all aspects of life, including employment, housing, family relations, and access to education and health care. Transgender persons were especially vulnerable to physical and psychological abuse and harassment.

During the year the NGO Public Information and Need of Knowledge (PINK Armenia) documented 27 cases of alleged human rights violations against LGBTI persons, but only four victims sought help from the ombudsperson's office and none from law enforcement bodies.

On 23 August, according to media reports, 30 to 35 civilian men, allegedly led by a municipality employee, attacked a group of transgender sex workers in a park near the municipality office. Police stopped the attack and opened a criminal investigation into the incident. Lawyers from the NGO New Generation, who represented the transgender persons and the sex workers, claimed that such group attacks happened at least once a month and individual attacks happened almost daily. In most cases, police were ineffective in either preventing such cases or apprehending perpetrators.

On 25 May, PINK Armenia placed three LGBTI-themed social advertising banners in downtown Yerevan. On 27 May, the advertising company tore them down following a highly negative public reaction. Shortly after the posters were removed, an official from the Yerevan municipality announced on his Facebook page that the three banners promoting tolerance were posted illegally and without the permission of the municipality. According to PINK Armenia, the banners did not contain any material prohibited by the law, the installation was made in accordance with existing practices, and the Yerevan municipality violated the NGO's freedom of expression. After the removal of the posters, anti-LGBTI groups launched cyberattacks on PINK Armenia's website. The physical address of PINK Armenia was posted on Facebook with a message encouraging attacks on the organization. On 9 July, the Golden Apricot International Film festival opened amid controversy over the organizers' canceling the screening of several noncompetitive films, including two with LGBTI themes. One of the festival's partners, the Union of Cinematographers, demanded that the two films be removed from the program. The festival organizers responded by canceling the screening of all noncompetitive-category films immediately before the festival's opening. According to an assessment conducted by the NGO New Generation in 2016, transgender individuals desiring to undergo sex-change procedures faced medical and other problems related to the administration of hormones without medical supervision, underground surgeries, and problems obtaining documents reflecting a change in gender identity.

On 4 July, the Right Side NGO, which focuses on the transgender population, reported that a local municipal employee came to their location to harass and assault its president. In September the president reported that the organization's landlord decided not to renew their lease.

Openly gay men are exempt from military service. An exemption, however, requires a medical finding based on a psychological examination indicating an individual has a mental disorder; this information appears in the individual's personal identification documents and is an obstacle to employment and obtaining a driver's license. Gay men who served in the army reportedly faced physical and psychological abuse as well as blackmail."[44] - HIV and AIDS Social Stigma

"According to human rights groups, persons regarded as vulnerable to HIV/AIDS, such as sex workers (including transgender sex workers) and drug users, faced discrimination and violence from society as well as mistreatment by police."[44] - Discrimination with Respect to Employment and Occupation

"There were no effective legal mechanisms to implement these regulations, and discrimination in employment and occupation occurred based on gender, age, presence of a disability, sexual orientation, HIV/AIDS status, and religion, even though there were no official or other statistics to account to the scale of such discrimination."[44]

Public opinion

[edit]A 2016 study by the Heinrich Böll Foundation found that only 9% of respondents knew anyone who was LGBT and 90% agreed with the statement, "Homosexual relationships should be banned by law".[45]

According to a June 2015-June 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center, 96% of Armenians opposed same-sex marriage, with only 3% supporting it.[46]

In May 2017, a survey by the Pew Research Center in Eastern European countries showed that 97% of Armenians believed that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[47]

According to a 2022 survey by the World Values Survey, 85% of Armenians believed that "homosexuality is never justified". The same survey found that 82% of Armenians "would not like to have homosexuals as neighbors".[48][49][50][51]

Summary table

[edit]| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (16) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment only | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in education | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Hate crime laws include sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriage legal | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Adoption by single people regardless of sexual orientation | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Third gender option | |

| Intersex minors protected from invasive surgical procedures | |

| Conversion therapy banned by law | |

| Gay panic defense banned by law | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Automatic parenthood for both spouses after birth | |

| Altruistic surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSM allowed to donate blood |

See also

[edit]- Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly–Vanadzor

- Human rights in Armenia

- ILGA-Europe

- LGBT rights by country or territory

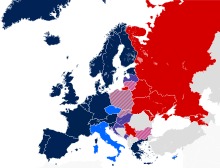

- LGBT rights in Europe

- LGBT rights in Asia

- Pink Armenia

- Recognition of same-sex unions in Armenia

- Recognition of same-sex unions in Europe

- Right Side NGO

- Social issues in Armenia

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "State-sponsored Homophobia A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults" (PDF). ILGA. May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Carroll, Quinn, Aengus, Sheila. "Forced Out: LGBT People in Armenia" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b PINK Armenia (7 December 2011). "ISSUU – Public opinion toward LGBT people in Yerevan, Gyumri and Vanadzor cities by PINK Armenia". Issuu. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Refworld – Armenian Gays Face Long Walk to Freedom". Refworld. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Hetq – News, Articles, Investigations". 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ https://rainbowmap.ilga-europe.org/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Refworld – The Leader in Refugee Decision Support". Refworld. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Over 80 Nations Support Statement at Human Rights Council on LGBT Rights » US Mission Geneva". Geneva.usmission.gov. 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Homepage". Helsinki Association for Human Rights (in Armenian). Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Homosexuals – Money source for the police" (PDF). 22 November 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ ռ/կ, Ազատություն (5 September 2015). "Armenian Constitution To Ban Same-Sex Marriage". azatutyun.com.

- ^ "Human Rights Situation in Armenia" (PDF). Public Information Need of Knowledge NGO. May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

2015 was a regressive year for LGBT people's rights in Armenia, since the newly accepted Constitution restricted marriage as a union only between a man and a woman

- ^ Dawn Ennis (5 December 2017). "Orthodox Christian Cleric Supports Same-Sex Marriage in Armenia". Los Angeles Blade.

- ^ "Father Vazken Movsesian Joins Equality Armenia Board". Asbarez. 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Equality Armenia". Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ LLC, Helix Consulting. "Armenia's legislation already bans same-sex marriages, no additional changes necessary: acting deputy minister – aysor.am – Hot news from Armenia". aysor.am.

- ^ "Глава Минюста Армении исключил, что государство признает однополые браки после ратификации Стамбульской конвенции". panorama (in Russian). 26 August 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (23 January 2024). "Armenia must act to prevent discrimination against LGBTI people" (PDF). Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Caucasus Watch (9 February 2024). "Chechen Man Fleeing Persecution Wins Legal Battle in Yerevan".

- ^ "Member". ILGA Europe. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Armenia: Gays Live with Threats of Violence, Abuse". EurasiaNet.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Bigots on Baghramian?: Parliament Members Continue Gay Debate". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ artmika (9 May 2012). "Unzipped: Gay Armenia". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Man throwing eggs over Elton John found in Yerevan". Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Hey Armenia, We Need to Talk". The Armenian Weekly. 17 August 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Networks, Hornet (6 August 2018). "This Tiny Armenian Town Formed a Lynch Mob Against Its LGBTQ Citizens, Injuring Many". Hornet.

- ^ "US embassy condemns hate crimes against LGBTI Armenians". news.am. 6 August 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Campaign To Raise Funds for LGBT Activists Attacked in Shurnukh". GALAS. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Following mob attack, LGBTQ activists in Armenia 'want justice'". NBC News. 8 August 2018.

- ^ https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/pink-armenia-rainbow-forum-lgbtiq-rights-activists-homophobia/

- ^ Ani Avetisyan (25 April 2023). "'An attack on the clubbing community': popular Yerevan club raided by police". OC Media.

- ^ ""I want to live": trans woman murdered in Armenia". Armenian Weekly. 23 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "About". Armenian Gay & Lesbian Association of NY. Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Փինք Արմենիա". Pink Armenia (in Armenian). Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Home". My Site.

- ^ Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (26 April 2019). "Armenian MPs call for trans activist to be burned alive after historic speech". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ Karasz, Palko (26 April 2019). "A Trans Woman Got 3 Minutes to Speak in Armenia's Parliament. Threats Followed". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ "Can transgender people speak in Armenia?".

- ^ Hovhannisyan, Irina (8 August 2013). "Armenian Bill on Gay 'Propaganda' Ban Withdrawn". «Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն» ռադիոկայան. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Hovhannisyan, Irina (8 August 2013). "Armenian Bill on Gay 'Propaganda' Ban Withdrawn". «Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն» Ռադիոկայան. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Amid threats, LGBT forum is cancelled in Armenia | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org.

- ^ Հովհաննես Գալաջյան. "ՆՐԱՆՔ ՍՊԱՍԱՐԿՈՒՄ ԵՆ ՄԻՋԱԶԳԱՅԻՆ ՀԱՄԱՍԵՌԱՄՈԼ ԼՈԲԲԻՆԳԻ ՇԱՀԵՐԸ. ԱԶԳԻ ԵՎ ՊԵՏՈՒԹՅԱՆ ԹՇՆԱՄԻՆԵՐԻ ՍԵՎ ՑՈՒՑԱԿԸ". iravunk.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "The Court of Appeal decision on the case against "Iravunk": The newspaper did not offend anyone". 5 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Armenia 2017 Human Rights Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ From Prejudice to Equality: Study of societal attitudes towards LGBTI people in Armenia (Report). Heinrich Böll Stiftung | Tbilisi – South Caucasus Region. 2016. ISBN 978-9939-1-0381-5.

- ^ "Support for same-sex marriage in Central and Eastern Europe | Surveys".

- ^ (in English) "Social views and morality". Religious belief and national belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Pew Research Center. 10 May 2017.

- ^ "Neighbors being homosexuals: Mentioned". ourworldindata.org. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Acceptance of homosexuals as neighbors". equaldex.com. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "LGBT Rights in Armenia". equaldex.com. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Justifiability of homosexuality". equaldex.com. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ https://www.arlis.am/documentview.aspx?docid=61097 [bare URL]

- ^ "Armenia: Events of 2023". Share this via Facebook. 11 January 2024.

External links

[edit]- "Human Rights Violations of LGBT People in Armenia: A Shadow Report" (PDF). Centre for Civil and Political Rights. Geneva. July 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "Official website of Pink Armenia" (in Armenian).

- "Official website of GALAS (Gay And Lesbian Armenian Society)".