Birth tourism

| Legal status of persons |

|---|

| Birthright |

| Nationality |

| Immigration |

Birth tourism is the practice of traveling to another country or city for the purpose of giving birth in that country. The main reason for birth tourism is to obtain citizenship for the child in a country with birthright citizenship (jus soli).[1] Such a child is sometimes called an "anchor baby" if their citizenship is intended to help their parents obtain permanent residency in the country. Other reasons for birth tourism include access to public schooling, healthcare, sponsorship for the parents in the future,[2] hedge against corruption and political instability in the children’s home country.[3] Popular destinations include the United States and Canada. Another target for birth tourism is Hong Kong, where some mainland Chinese citizens travel to give birth to gain right of abode for their children.

In an effort to discourage birth tourism, Australia, France, Pakistan, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom have modified their citizenship laws at different times, mostly by granting citizenship by birth only if at least one parent is a citizen of the country or a legal permanent resident who has lived in the country for several years. Germany has never granted unconditional birthright citizenship, but has traditionally used jus sanguinis, so, by giving up the requirement of at least one citizen parent, Germany has softened rather than tightened its citizenship laws.

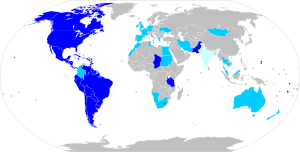

Since the Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 2004, no European country presently grants unconditional birthright citizenship;[4][5] however, most countries in the Americas, e.g., the United States, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil do so. In Africa, Chad, Lesotho and Tanzania grant unconditional birthright citizenship,[6] as do some in the Asian-Pacific region including Fiji, Pakistan, and Tuvalu. [citation needed][7]

Today

[edit]North America

[edit]The United States, Canada, and Mexico all grant unconditional birthright citizenship and allow dual citizenship. The United States taxes its citizens and green card holders worldwide, even if they have never lived in the country. In Mexico, only naturalized citizens can lose their Mexican citizenship again (e.g., by naturalizing in another country).

United States

[edit]The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was ratified after the Civil War to ensure that the freed slaves along with their children would get American citizenship,[1] guarantees U.S. citizenship to those born in the United States, provided the person is "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States.[8] Congress has further extended birthright citizenship to all inhabited U.S. territories except American Samoa. (A person born in American Samoa becomes a non-citizen US national). The parent(s) and child are still subject to de jure and de facto deportation, respectively.[9] However, once they reach 21 years of age, American-born children, as birthright citizens, are able to sponsor their foreign families' U.S. citizenship and residency.[10][3]

There are no statistics about the 7,462 births to foreign residents in the United States in 2008,[1] the most recent year for which statistics are available. That is a small fraction of the roughly 4.3 million total births that year.[11]

Russian birth tourism to Florida to 'maternity hotels' in the 2010s is documented.[10][12][13] Birth tourism packages complete with lodging and medical care delivered in Russian begin at $20,000, and go as high as $84,700 for an apartment in Miami's Trump Tower II complete with a "gold-tiled bathtub and chauffeured Cadillac Escalade."[13]

One option for mainland Chinese mothers to give birth is Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands, where the cost is cheaper and travel does not require a U.S. visa.[14] More than 70% of the newborns in Saipan have birth tourist PRC parents who take advantage of the 45-day visa-free visitation rules of the territory and the Covenant of the Northern Mariana Islands to ensure that their children can have American citizenship. There were 282 of these births in 2012.[15] At least one airline in Hong Kong requests that women who are "observed to have a body size or shape resembling a pregnant woman" submit to a pregnancy test before they are allowed to fly to Saipan.[16]

As of 2015[update], Los Angeles is considered a center of the maternity tourism industry, which caters mostly to women from China and Taiwan;[3] authorities in the city there closed 14 maternity tourism "hotels" in 2013.[17] The industry is difficult to close down since it is not illegal for a pregnant woman to travel to the U.S.[17] On March 3, 2015, Federal agents in Los Angeles conducted a series of raids on three "multimillion-dollar birth-tourism businesses" expected to produce the "biggest federal criminal case ever against the booming 'anchor baby' industry", according to The Wall Street Journal.[17][18][19]

Numerous "maternity businesses" advise pregnant mothers to hide their pregnancies from officials and commit visa fraud—lying to customs agents about their true purpose in the U.S.[20] Once they give birth, several 'birth tourism' agencies aid the mothers in defrauding the U.S. hospital, taking advantage of discounts reserved for impoverished American mothers.[21][22] Some mothers will refuse to pay the bill for the medical care received during their hospital stay.[23]

On October 18, 2014, the North American Chinese language Daily World Journal reported that for several weeks the immigration authorities at LAX had been closely questioning pregnant Chinese women arriving there from China, and in many cases denying them entry to the United States and repatriating them within 12 hours, often on the same airplane on which they had flown to the United States.[24] In March 2015, federal agents conducted raids on a series of large-scale maternity tourism operations bringing thousands of mainland Chinese women intent on giving their children American citizenship.[17][18] Congressional representatives such as Phil Gingrey, who have tried to put an end to birth tourism, said these people are "gaming the system".[25] In August 2015, the issue was discussed among U.S. presidential candidates, including Donald Trump and Jeb Bush.

In January 2019, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement investigations led to the arrest of three southern California operators of "multimillion-dollar birth-tourism businesses" catering primarily to Chinese nationals.[26]

Effective January 24, 2020, a new policy was adopted that made it more difficult for pregnant foreign women to come to the US to give birth on US soil to ensure their children become US citizens. The country will no longer issue temporary B-1/B-2 visitor visas to applicants seeking to enter the United States for birth tourism.[27][28]

In December 2020, federal prosecutors charged six Long Island residents who were operating a birth tourism scheme that cost U.S. taxpayers over $2 million. The suspects submitted over 99 Medicaid claims for different women, assisting the births of about 119 children who now have U.S. citizenship. The suspects were charged with conspiracy to commit health care fraud, visa fraud, wire fraud and money laundering.[29]

Worldwide taxation of U.S. citizens and permanent residents

[edit]

The United States, Eritrea, Hungary, Myanmar, and Tajikistan are currently the only countries in the world to tax their citizens worldwide, even if they have never lived in the country and were born to citizens living abroad.[30] (see International taxation)

A U.S.-born person is, as a citizen, automatically subject to U.S. taxation. This is true even if both parents are non-U.S. citizens, their child holds multiple citizenships, and the family leaves the U.S. right after the child's birth and never returns again. Children born to U.S. citizens living abroad are also automatically subject to U.S. taxation, even if he/she never enters the U.S.

U.S. permanent residents are also subject to worldwide taxation. Worldwide taxation is often cited as a reason for U.S. citizens or permanent residents to relinquish their citizenship or residency status.[30]

Fee for renunciation of U.S. citizenship

[edit]In 2015, the fee for renunciation of U.S. citizenship was raised by 422%. It went from US$450 to $2,350 and is the highest fee for the renunciation of a citizenship worldwide.[31]

Canada

[edit]Canada's citizenship law has, since 1947, generally conferred Canadian citizenship at birth to anyone born in Canada, regardless of the citizenship or immigration status of the parents. The only exception is for children born in Canada to representatives of foreign governments or international organizations. The Canadian government has considered limiting jus soli citizenship,[32] and as of 2012[update] continues to debate the issue[33] but has not yet changed this part of Canadian law.

Some expectant Chinese parents who have already had one child travel to Canada to give birth in order to circumvent China's one-child policy,[34] additionally acquiring Canadian citizenship for the child and applying for a passport before returning to China.

A Québec birth certificate entitles a student enrolled in that province to pay university tuition at the lower in-province rate;[35] on average this was $3760/year in 2013.[36]

Mexico

[edit]Mexicans who are citizens by birth are individuals that were born in Mexican territory regardless of parents' nationality or immigration status in Mexico. Individuals born on Mexican merchant or Navy ships or Mexican-registered aircraft, regardless of parents' nationality, are still considered Mexican citizens. Only naturalized Mexicans can lose their Mexican citizenship.

Birth (and abortion and other medical) tourism among the United States, Canada, and Mexico

[edit]In the Canada–US border region, the way to a hospital in the neighboring country is sometimes shorter than to a hospital in the patient's own country. So, Canadian women sometimes give birth to their children in U.S. hospitals, and U.S. women in Canadian hospitals. These children (sometimes called "border babies") are usually dual citizens of both the country of their parents and their birth country.

Canada has entered the medical tourism field.[37] In comparison to U.S. health costs, medical tourism patients can save 30 to 60 percent on health costs in Canada.

Mexican women sometimes engage in birth tourism to the United States or Canada to give their children U.S. or Canadian citizenship.

While some non-legal obstacles exist, Canada is one of only a few countries without legal restrictions on abortion. Regulations and accessibility vary between provinces.

In the United States, different states have different abortion laws, so that women in states with restrictive laws sometimes engage in abortion tourism, either to the U.S. states with more liberal laws, to Mexican states with liberal laws, or to Canada.

South America

[edit]Most South American countries grant unconditional birthright citizenship and allow dual citizenship, however, some countries have strict abortion laws that make them risky birth-tourism destinations in case of complications during the pregnancy. In Brazil, abortion is illegal with exception to cases of rape, incest or if the mother's life is in danger.[38] It is restricted to cases of maternal life, mental health, health, rape, or fetal defects. In Chile, abortion was forbidden completely, even if the pregnant woman's life is in danger until 2017. Current law allows abortion in Chile only if the mother's life is in danger, if the fetus is inviable and in rape cases.

Some countries do not allow their citizens to renounce their citizenship or only if the citizenship was acquired by birth there to non-citizen parents. In Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Uruguay, voting is compulsory for citizens. In Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Venezuela, military service is mandatory.

Argentina

[edit]Any person born in Argentine territory acquires Argentine citizenship at birth,[39] excepting children of persons in the service of a foreign government (e.g. foreign diplomats). This can be also applied to people born in the Falkland Islands, a disputed territory between Argentina and the United Kingdom. Argentine citizens cannot renounce their Argentine citizenship.

Brazil

[edit]A person born in Brazil acquires Brazilian citizenship at birth, regardless of their parents' ancestry.[40] It is said Brazilian citizens cannot renounce their Brazilian citizenship, but it is possible to renounce it through a requirement made in the Brazilian consulate if they already have acquired another citizenship voluntarily. Foreign tourists, parents of a Brazilian child, may apply for permanent residency in Brazil based on their child's nationality.[41]

Chile

[edit]As of 2023, all children born in Chile acquire Chilean citizenship at birth, the only exception being children born of people working for foreign diplomatic missions. Chilean Supreme Court ruled that children of irregular immigrants are not to be considered "Transient foreigners" and therefore receive Chilean citizenship as well.[42]

Paraguay

[edit]Any person born in Paraguay territory acquires Paraguayan citizenship at birth. The only exception applies to children of persons in the service of a foreign government (like foreign diplomats).

Hong Kong

[edit]As a non-sovereign territory, Hong Kong does not have its own citizenship; the status akin to citizenship in Hong Kong is the right of abode, also known as permanent residence. Hong Kong permanent residents regardless of citizenship are accorded all rights normally associated with citizenship, with few exceptions such as the right to a HKSAR passport and the eligibility to be elected as the chief executive which are only available to Chinese citizens with right of abode in Hong Kong.

According to the Basic Law of Hong Kong, Chinese citizens born in Hong Kong have the right of abode in the territory. The 2001 court case Director of Immigration v. Chong Fung Yuen affirmed that this right extends to the children of mainland Chinese parents who themselves are not residents of Hong Kong.[43] As a result, there has been an influx of mainland mothers giving birth in Hong Kong in order to obtain right of abode for the child. In 2009, 36% of babies born in Hong Kong were born to parents originating from Mainland China.[44] This has resulted in backlash from some circles in Hong Kong to increased potential stress on the territory's social welfare net and education system.[45] Attempts to restrict benefits from such births have been struck down by the territory's courts.[44] A portion of the Hong Kong population has reacted negatively to the phenomenon, which has exacerbated social and cultural tensions between Hong Kong and mainland China. The situation came to a boiling point in early 2012, with Hong Kongers taking to the street to protest the influx of birth tourism from mainland China.[citation needed]

In the past (stopped by changes in laws)

[edit]Malta

[edit]Malta changed the principle of citizenship to jus sanguinis on 1 August 1989 in a move that also relaxed restrictions against multiple citizenships.

India

[edit]Because of an enormous population[citation needed], India abolished jus soli on 3 December 2004. This was in response to the fear of having mass immigration from Bangladesh.[46] Jus soli had already been progressively weakened in India since 1987.

India allows a form of "overseas citizenship", but no real dual citizenship. In 2005, India introduced a new category of permanent residency which allowed people of Indian descent to live and work in the country.[47]

Ireland

[edit]Irish nationality law conveyed birthright citizenship to anyone born anywhere on the island of Ireland (including in Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom) until the 27th Amendment was passed by referendum in 2004. The amendment was preceded by media reports of heavily pregnant women claiming political asylum, who expected that, even if their application was rejected, they would be allowed to remain in the country if their new baby was a citizen.[48] Irish birthright citizenship could also serve for immigration purposes abroad: the case of Chen v Home Secretary involved a Chinese woman living temporarily in the UK who travelled to Belfast to give birth, for the purpose of using her daughter's Irish (and thus European Union) citizenship to obtain the permanent right to reside in the UK as a parent of a dependent EU citizen. Until 2004, Ireland was the last European country to grant unconditional birthright citizenship.

Ireland retains jus soli citizenship for people born anywhere on the island of Ireland with at least one parent who is (i) Irish; (ii) British; (iii) has the right to live permanently in Ireland or Northern Ireland (e.g. EU citizens); or (iv) has resided legally in Ireland or Northern Ireland for at least 3 of the 4 years preceding the child's birth (time spent as an asylum seeker does not count). The island of Ireland is expected to become an attractive birth tourism destination post-Brexit for British people from England, Wales and Scotland since the child is entitled to Irish citizenship and thus EU citizenship.[49]

Dominican Republic

[edit]The constitutional court of the Dominican Republic reaffirmed in TC 168-13 that children born in the Republic from individuals that were "in transit" are excluded from Dominican citizenship as per the Dominican Republic's constitution. The "in-transit" clause includes those individuals residing in the country without legal documentation, or with expired documentation. TC 168-13 also required the civil registry to be cleaned from abnormalities going as far back as 1929, when the "in-transit" clause was first put in place in the constitution. The Dominican government does not consider it a retroactive decision but only a reaffirmation of a clause that has been present in every revision of the Dominican constitution as far back as 1929.

Encouraged by jus-soli countries (in the past)

[edit]In former times, some countries (Latin American countries and Canada) advertised their policy of unconditional birthright citizenship to become more attractive for immigrants.[citation needed]

Birth- and pregnancy tourism to non-jus-soli countries

[edit]

Some women engage in birth tourism not to give their children a foreign citizenship, but because the other country has a better or cheaper medical system or allows procedures that are forbidden in the women's home countries (e.g. in-vitro fertilization, special tests on fetuses and embryos, or surrogacy).

But this may lead to legal problems for the babies in the home country of their future parents. For example, Germany, like 14 other EU countries, forbids surrogacy, and a baby born abroad to a foreign surrogate mother has no right to German citizenship. According to German law, the woman who gives birth to a baby is its legal mother, even if it is not genetically related to her, and if the foreign surrogate mother is married, her husband is regarded as the legal father.

Many women travel abroad only for some procedures forbidden in their home countries, but then return to their home countries to give birth to their children ("pregnancy tourism").

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Born in the U.S.A.: Birth tourists get instant U.S. citizenship for their newborns". NBC News. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Grant, Tyler. "MADE IN AMERICA: MEDICAL TOURISM AND BIRTH TOURISM LEADING TO A LARGER BASE OF TRANSIENT CITIZENSHIP" (PDF). Virginia Journal of Social Policy & the Law. 22 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ a b c "From the Archives: In suburbs of L.A., a cottage industry of birth tourism". Los Angeles Times. 3 January 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

USA Baby Care's website makes no attempt to hide why the company's clients travel to Southern California from China and Taiwan. It's to give birth to an American baby.

- ^ Gilbertson, Greta (1 January 2006). "Citizenship in a Globalized World". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Vink, M.; de Groot, G.R. (2010). Birthright Citizenship: Trends and Regulations in Europe. Comparative Report RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-Comp. 2010/8 (PDF). Florence: EUDO Citizenship Observatory. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Manby, Bronwen (2016). Citizenship law in Africa: a comparative study (3rd ed.). New York, NY: African Minds on behalf of Open Society Foundations. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-928331-08-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Dziedzic, Anna (February 2020). "Comparative Regional Report on Citizenship Law: Oceania" (PDF). Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ "Made in Russia, born in America: birth tourism booming in Miami". NBC News. 10 January 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ "The myth of the 'anchor baby' deportation defense". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b A.J. Delgado, "Instant Citizens", National Review, May 2, 2015.

- ^ Medina, Jennifer (28 March 2011). "Officials Close 'Maternity Tourism' House in California". The New York Times.

- ^ McFadden, Cynthia (10 January 2018). "Birth tourism brings Russian baby boom to Miami". NBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b Savadski, Katie (6 September 2017). "Russians Flock to Trump Properties to Give Birth to U.S. Citizens". Daily Beast. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ South China morning post. "Mainland moms look West after Hong Kong backlash". 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Rise in number of Chinese 'birth tourists' to Saipan". www.wantchinatimes.com. 13 February 2014. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Emont, Jon (10 January 2020). "An Airline Required a Woman to Take a Pregnancy Test to Fly to This U.S. Island". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Jordan, Miriam (3 March 2015). "Federal Agents Raid Alleged 'Maternity Tourism' Businesses Catering to Chinese". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ a b Kim, Victoria (3 March 2015). "Alleged Chinese 'maternity tourism' operations raided in California". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Asian 'anchor babies': Wealthy Chinese come to Southern California to give birth". Los Angeles Times. 26 August 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Abby Phillip, "Inside the Shadowy World of Birth Tourism at 'Maternity Hotels'", The Washington Post, March 5, 2015.

- ^ Sheehan, Matt (1 May 2015). "Born In The USA: Why Chinese 'Birth Tourism' Is Booming In California". Retrieved 29 May 2017 – via Huff Post.

- ^ Matt Sheehan, "Born in the USA: Why Chinese 'Birth Tourism' is Booming in California", The World Post, May 14, 2015.

- ^ "Born In The USA: Why Chinese 'Birth Tourism' Is Booming In California". Huffington Post. 1 May 2015.

- ^ page 1, World Journal, October 18, 2014

- ^ "Rock Center with Brian Williams - Born in the U.S.A.: Birth tourists get instant U.S. citizenship for their newborns". MSNBC. 28 October 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Miriam Jordan (1 January 2019). "3 Arrested in Crackdown on Multimillion-Dollar 'Birth Tourism' Businesses". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

Grand jury indictments unsealed Thursday in Federal District Court in Los Angeles brought the total number of people charged in the schemes to 19, including both business operators and clients. But some of those targeted in the indictments were not presently in the United States, investigators said. ... The number of businesses in operation is undoubtedly much larger than the three agencies targeted in the latest indictments in the Los Angeles area, said Mark Zito, assistant special agent in charge of Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Homeland Security Investigations in Los Angeles.

- ^ "US imposes new 'birth tourism' visa rules for pregnant women". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

Applicants will be denied tourist visas if they are determined by consular officers to be coming to the US primarily to give birth, according to the rules in the Federal Register.

- ^ US issues new rules restricting travel by pregnant foreigners, fearing the use of 'birth tourism'

- ^ "6 charged in 'birth tourism' scheme that cost U.S. taxpayers millions". NBC News. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b "U.S. Citizens and Resident Aliens Abroad". www.IRS.gov. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Wood, Robert W. (23 October 2015). "U.S. Has World's Highest Fee To Renounce Citizenship". Forbes. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ Thomas Alexander Aleinikoff; Douglas B. Klusmeyer (2002). Citizenship policies for an age of migration. Carnegie Endowment. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-87003-187-8.

- ^ Prithi Yelaja (5 March 2012). "'Birth tourism' may change citizenship rules". CBC News.

- ^ "Chinese 'birth tourists' having babies in Canada". CBC News. 18 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Quebec residency situations". www.Concordia.ca. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Habib, Marlene (11 September 2013). "University tuition rising to record levels in Canada". CBC News.

- ^ "Medical Tourism: Travel to Another Country for Medical Care | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov.

- ^ Davies, Sophie (26 May 2016). "Faced with strict laws, Brazilian women keep abortions secret". Reuters.

Roughly one million women each year seek abortions to end unwanted pregnancies in Brazil, where abortion is illegal except in cases of rape or incest or if the life of the mother is in danger.

- ^ Aires, Buenos. "Argentina cracks down on 'birth tourism' as pregnant Russian women flock for citizenship". WION. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "Give birth in Brazil - how does it work?". LiveInBrazil.net. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Obtain a Brazilian Citizenship". The Brazil Business. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Convenciones sobre estatutos de los apátridas". Senado.cl.

- ^ Chen, Albert H. Y. (2011), "The Rule of Law under 'One Country, Two Systems': The Case of Hong Kong 1997–2010" (PDF), National Taiwan University Law Review, 6 (1): 269–299, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2016, retrieved 4 October 2011

- ^ a b "Mamas without borders". The Economist. 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Hong Kong Maternity Tourism". Sinosplice. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ "Accident of birth". The Indian Express. 3 November 2018.

- ^ Yeung, Jessie (15 March 2021). "These Asian countries are giving dual citizens an ultimatum on nationality -- and loyalty". CNN. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ Mancini, J. M.; Graham Finlay (September 2008). ""Citizenship Matters": Lessons from the Irish Citizenship Referendum" (PDF). American Quarterly. 60 (3): 575–599. doi:10.1353/aq.0.0034. ISSN 1080-6490. S2CID 145757112.

- ^ "How birth in Northern Ireland enables dual nationality". 25 September 2019.