List of awards and honours received by Winston Churchill

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Liberal Government

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

First Term

Second Term

Books

|

||

Winston Churchill received numerous honours and awards throughout his career as a British Army officer, statesman and author.

Perhaps the highest of these was the state funeral held at St Paul's Cathedral, after his body had lain in state for three days in Westminster Hall,[1] an honour rarely granted to anyone other than a British monarch. Queen Elizabeth II also broke protocol by giving precedence to a subject, arriving at the cathedral ahead of Churchill's coffin.[2] The funeral also saw one of the largest assemblages of statesmen in the world.[3]

Throughout his life, Churchill also accumulated other honours and awards. He was awarded 37 other orders and medals between 1895 and 1964. Of the orders, decorations and medals Churchill received, 20 were awarded by the United Kingdom, three by France, two each by Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg and Spain, and one each by the Czech Republic, Egypt, Estonia, Libya, Nepal, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United States. Ten were awarded for active service as a British Army officer in Cuba, India, Egypt, South Africa, the United Kingdom, France, and Belgium. The greater number of awards were given in recognition of his service as a minister of the British government.[4]

Coat of arms

[edit]Churchill was not a peer, never held a title of nobility, and remained a commoner all his life. As a male-line grandson of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, he bore (by courtesy) the quartered coat of arms of the Spencer and Churchill families, as the Spencer-Churchills had done since the time of Charles Spencer, 3rd Duke of Marlborough. Paul Courtenay observed that "It would be normal in [Charles Spencer's] circumstances for the paternal arms (Spencer) to take precedence over the maternal (Churchill), but because the Marlborough dukedom was senior to the Sunderland earldom, the procedure was reversed in this case."[5] In 1817, an augmentation of honour was granted commemorating the victory at Blenheim by the 1st Duke of Marlborough.[6]

As Churchill's father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was the second surviving son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, his arms should have been differenced, according to strict heraldic rules, with a mark of cadency. Traditionally, this would have been a heraldic crescent, and those differenced arms would have been inherited by Winston Churchill. However, such differenced arms do not appear to have been adopted by Lord Randolph or Winston.

Although arms are supposed to differentiate between bearers, there does not seem to have been any confusion between Churchill's armorial achievement as an untitled gentleman with many decorations (and later a Knight Companion of the Garter), that of his brother as a plain gentleman, and that of his cousin, the Duke of Marlborough, which had the heraldic adornments of a duke. As a Knight Companion of the Garter, Churchill was also entitled to supporters in his achievement, but he never seems to have got around to applying for them.[5]

The blazon of the arms is: quarterly 1st and 4th, Sable a lion rampant Argent on a canton of the second a cross Gules (Churchill); 2nd and 3rd, quarterly Argent and Gules, in the second and third quarters a fret Or, over all on a bend Sable three escallops of the first (Spencer); in chief, on an escutcheon Argent a cross Gules surmounted by an inescutcheon Azure charged with three fleurs-de-lys Or.[5]

When Churchill became a Knight Companion of the Garter in 1953, his arms were encircled by the garter of the order. At the same time, the helms were made open, which is the mark of a knight. His motto was that of the Dukes of Marlborough, which is Fiel pero desdichado (Spanish for 'Faithful but unfortunate').[7]

-

Armorial achievement of Churchill as a gentleman

-

Armorial achievement of Churchill as a Knight Companion of the Garter

-

Armorial achievement of Churchill as a Knight of the Danish Order of the Elephant

-

The shield of arms on its own

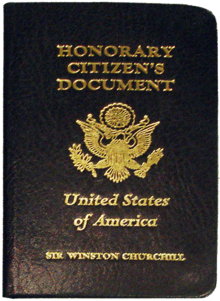

Honorary citizen

[edit]

On 9 April 1963, United States President John F. Kennedy, acting under authorization granted by an Act of Congress, proclaimed Churchill the first honorary citizen of the United States. Churchill was physically incapable of attending the White House ceremony, so his son and grandson accepted the award for him.[8][9]

He had previously been made an honorary citizen of the City of Paris on 12 November 1944 while visiting the city following the liberation. During the ceremony at the Hôtel de Ville, he received the Nazi flag that once flew from the Hôtel de Ville.[10]

Proposed dukedoms

[edit]In 1945, King George VI offered to make Churchill the Duke of Dover – the first non-royal dukedom to be created since 1874 – and appoint him as a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter; however, Churchill turned down both.[11][12] Since 1900, only members of the British royal family have been made dukes, so the offer was exceptional.[13]

In 1955, after retiring as prime minister, Churchill was again offered elevation to the peerage in the rank of duke by Queen Elizabeth II. By custom, prime ministers retiring from the Commons were usually offered earldoms, so a dukedom was a sign of special honour. One title that was considered was Duke of London, a city whose name had never been used in a peerage title. Churchill had represented divisions of three different counties in Parliament, and his home, Chartwell, was in a fourth, so the city in which he had spent most of his time during fifty years in politics was seen as a suitable choice. Churchill considered accepting the offer of a dukedom but eventually declined it; the lifestyle of a duke would have been expensive, and accepting any peerage might have cut short a renewed career in the Commons for his son Randolph, and in due course, might also have prevented one for his grandson Winston.[14] At the time, there was no procedure for disclaiming a title; the procedure was first established by the Peerage Act 1963. Upon inheriting a peerage, either Randolph or Winston would have been unseated immediately from the House of Commons.[15]

Political and government offices

[edit]- Member of Parliament (1901–1922, 1924–1964)

- Under Secretary of State for the Colonies (1905–1908)

- Privy Counsellor (1907–1965)[16]

- President of the Board of Trade (1908–1910)

- Home Secretary (1910–1911)

- First Lord of the Admiralty (1911–1915, 1939–1940)

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1915)[16]

- Minister of Munitions (1917–1919)

- Minister of Defence (1940-1945)

- Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air (1919–1922)

- Chancellor of the Exchequer (1924–1929)

- First Lord of the Admiralty (1939–1940)

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1940–1945, 1951–1955)

- Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1941–1965)[17]

- Member of the King's Privy Council for Canada (29 December 1941 – 1965)[18]

- Leader of the Opposition (1945–1951)

- Father of the House of Commons (1959–1964)

Other honours

[edit]

In 1913, Churchill was appointed an Elder Brother of Trinity House as result of his appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty.[19]

In 1922, he was invested as a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour and in 1946 he became a Member of the Order of Merit. In 1953, he was invested as a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter, the highest ranking British order of knighthood.

On 4 April 1939, Churchill was made an Honorary Air Commodore of No. 615 (County of Surrey) Squadron ("Churchill's Own") in the Auxiliary Air Force.[20] In March 1943, the Air Council awarded Churchill honorary wings.[13] He retained the appointment until 11 March 1957 when 615 Squadron was disbanded. He did, however, continue to hold the rank of Honorary Air Commodore.[21] He frequently wore his uniform as an Air Commodore during World War II.

He was the Colonel of the 4th Queen's Own Hussars (his old regiment) and, after its amalgamation, the first Colonel of the Queen's Royal Irish Hussars, which he held until his death in 1965. He was also Honorary Colonel of the Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars.[22][23]

From 1941 to his death, he was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a ceremonial office. In 1941, Canadian Governor General Alexander Cambridge, Earl of Athlone, swore him into the King's Privy Council for Canada. Although this allowed him to use the honorific title The Honourable and the post-nominal letters PC, both of these were trumped by his membership in the Imperial Privy Council, which allowed him the use of The Right Honourable.[13] He was also appointed Grand Seigneur of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1956.[24]

In 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates that were qualified for the Nobel Peace Prize. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. Actually, he nominated Cordell Hull.[25]

On 4 July 1947, Churchill was admitted as an hereditary member of the Connecticut Society of the Cincinnati. He was presented with his insignia and diploma when he visited Washington, D.C., on January 16, 1952.[26]

A prolific painter in oils, in 1948 he was elected as an Honorary Academician Extraordinary by the Royal Academy: a highly unusual honour for an amateur artist.[27]

In 1949, Churchill held the office of Deputy Lieutenant (DL) of Kent.[28]

In 1953, he was made a Knight Companion of the Garter, which gave him the title Sir Winston Churchill, KG. He also won the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending high human values."[29]

He was Chancellor of the University of Bristol, as well as, in 1959, Father of the House, the MP with the longest continuous service.[30]

In 1956, Churchill received the Karlspreis (known in English as the Charlemagne Award), an award by the German city of Aachen to those who most contribute to the European idea and European peace.[31]

The Royal Society of Literature made Churchill one of the first five authors to be named a Companion of Literature in 1961.[32]

Also in 1961, the Chartered Institute of Building[33] named Churchill as an Honorary Fellow for his services and passion for the construction industry.

In 1964, Civitan International presented Churchill with its first World Citizenship Award for service to the world community.[34]

Churchill was also appointed a Kentucky Colonel.[35][36]

When Churchill was 88, he was asked by the Duke of Edinburgh how he would like to be remembered. He replied with a scholarship like the Rhodes scholarship but for the wider masses. After his death, the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust was established in the United Kingdom and Australia. A Churchill Trust Memorial Day was held in Australia, raising $4.3 million. Since that time, the Churchill Trust in Australia has supported over 3,000 scholarship recipients in a diverse variety of fields, where merit, either on the basis of past experience or potential, and the propensity to contribute to the community, have been the only criteria.[citation needed]

One of the four sets of false teeth that Winston Churchill wore his whole life to keep his unique way of speaking is now in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in England.[37]

Namesakes

[edit]Ships, trains and tanks

[edit]

Two warships, from the UK and USA have been named HMS Churchill: the destroyer USS Herndon (I45) (1940–1944) and the submarine HMS Churchill (1970–1991).

On 10 March 2001, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Winston S. Churchill (DDG-81) was commissioned into the United States Navy. The launch and christening of the ship two years earlier had been co-sponsored by Churchill's daughter, Lady Soames.[38]

In addition, the Danish DFDS line named a car ferry Winston Churchill, and the Corporation of Trinity House named one of their lighthouse tenders similarly. A sail training ship was named Sir Winston Churchill.

In September 1947, the Southern Railway named a Battle of Britain class steam locomotive, No. 21C151, after him. Churchill was offered the opportunity to perform the naming ceremony, but he declined. Later, the locomotive was used to pull his funeral train, and it is now kept in York's National Railway Museum.

The Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway locomotive No. 9, Winston Churchill.

The Churchill tank, or Infantry Tank Mk IV; was a British Second World War tank named after Churchill, who was Prime Minister at the time of its design.[39]

Parks and geographic features

[edit]The Winston Churchill Range in the Canadian Rockies was named in his honour. Also in Canada, Sir Winston Churchill Provincial Park and Churchill Lake in Saskatchewan were named after him, and Churchill Falls on the Churchill River in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Winston Churchill Square is a garden and sitting area in Manhattan, New York City.

Churchill Park, Glendowie, New Zealand was created in 1945 and is anmed after him.

The Churchill National Park in Australia, which was established on 12 February 1941 as the Dandenong National Park, was renamed in 1944 in his honour. Churchill Island and Churchill Island Marine National Park in Victoria, Australia were also named after him.

The Churchill Park (Danish: Churchillparken) located in central Copenhagen, Denmark, is named after Churchill in commemoration of Churchill and the British help to Denmark in the liberation of Denmark during World War II.

Roads

[edit]![]() Belgium:

Belgium:

- Avenue Winston Churchill/Winston Churchilllaan in Brussels-Capital Region runs in the Municipality of Uccle/Ukkel.

- Rond-point Winston Churchill/Winston Churchillplein in Brussels-Capital Region runs in the Municipality of Uccle/Ukkel.

![]() United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Winston Churchill Avenue is a major road in Portsmouth.

- Winston Churchill Road is a minor road in King's Lynn.

- Basingstoke and Salford both have roads called Churchill Way.

![]() Canada:

Canada:

- The south end of Churchill Avenue in Ottawa was the site of the Churchill Arms Motor Hotel, which many residents of Ottawa remember for its three-storey exterior painting of the silhouette of Winston Churchill.[40] Churchill Avenue was itself renamed from Main Street after the Second World War.

- In St. Albert, Alberta Sir Winston Churchill Ave runs east to west through the city.

- Winston Churchill Boulevard in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada is also named in his honour.

![]() France:

France:

- Avenue Winston-Churchill in Paris bordered by Grand and Petit Palais.

![]() Gibraltar: The main road connecting the border with Spain and the airport to the city centre is called Winston Churchill Avenue.

Gibraltar: The main road connecting the border with Spain and the airport to the city centre is called Winston Churchill Avenue.

![]() Germany: In Beuel, part of the city Bonn (former capital of West Germany), there is a "Winston-Churchill-Straße".

Germany: In Beuel, part of the city Bonn (former capital of West Germany), there is a "Winston-Churchill-Straße".

![]() Netherlands: In the Netherlands, about ninety roads and streets are named after Winston Churchill, including Churchilllaan, a major avenue in Leiden (part of the N206 road) and Churchill-laan, an avenue in Amsterdam.[41]

Netherlands: In the Netherlands, about ninety roads and streets are named after Winston Churchill, including Churchilllaan, a major avenue in Leiden (part of the N206 road) and Churchill-laan, an avenue in Amsterdam.[41]

![]() New Zealand: The main road through Crofton Downs, a suburb of Wellington is named Churchill Drive. Several streets in the Suburb are named after Winston Churchill (including Winston Street and Spencer Street,) family members (including Randolph Road and Clementine Way,) or other connections to Churchill (including Downing Street, Chartwell Drive and Admirialty Street.) [42]

New Zealand: The main road through Crofton Downs, a suburb of Wellington is named Churchill Drive. Several streets in the Suburb are named after Winston Churchill (including Winston Street and Spencer Street,) family members (including Randolph Road and Clementine Way,) or other connections to Churchill (including Downing Street, Chartwell Drive and Admirialty Street.) [42]

![]() Norway: Streets in the cities of Trondheim and Tromsø are named in Winston Churchill's honour. Namely "Churchills vei"[43] in Jakobsli, Trondheim and "Winston Churchills vei" in Tromsø.

Norway: Streets in the cities of Trondheim and Tromsø are named in Winston Churchill's honour. Namely "Churchills vei"[43] in Jakobsli, Trondheim and "Winston Churchills vei" in Tromsø.

![]() Brazil:

Brazil:

- Av. Churchill - Centro, Rio de Janeiro - Rio de Janeiro;

- Av. Churchill, Centro, Niterói -Rio de Janeiro ;

- Av. Churchill, Santa Efigênia, Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais;

- Av. Winston Churchill, Fugmann, Londrina - Paraná;

- Av. Winston Churchill, Capão Raso, Curitiba - Paraná;

- Av. Winston Churchill, Rudge Ramos, São Bernardo do Campo - São Paulo;

- Av. Winston Churchill, Parque Centenário, Duque de Caxias - Rio de Janeiro;

- Rua Churchill, Vila São Jorge, Nova Iquaçu - Rio de Janeiro;

- Rua Churchill, Cascatinha, Nova friburgo - Rio de Janeiro;

- Rua Churchill, Jardim Nakamura, São Paulo - São Paulo;

- Rua Churchill, Cruz, Lorena - São Paulo;

- Rua Churchill, Iririú, Joinville - Santa Catarina;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Jardim São Caetano, São Caetano do Sul - São Paulo;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Jardim das Industrias, São José dos Campos - São Paulo;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Bela Vista, Salto - São Paulo;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Presidente Prudente - São Paulo;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Solo Sagrado, São José do Rio Preto - São Paulo;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Vila São José, Nova Lima - Minas Gerais;

- Rua Winston Churchill, Cidade Nobre, Ipatinga - Minas Gerais;

- Rua Winston Churchill,Cavaleiros, Macaé - Rio de Janeiro;

- Rua Winston Churchill,Centro, Viana - Espírito Santo.

![]() Israel: Streets in the cities of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Netanya and Daliyat al-Karmel are named in Winston Churchill's honour.

Israel: Streets in the cities of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Netanya and Daliyat al-Karmel are named in Winston Churchill's honour.

Schools

[edit]Many schools have been named after him.

Ten schools in Canada are named in his honour: one each in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Hamilton, Kingston, St. Catharines, Lethbridge, Calgary, Toronto (Scarborough) and Ottawa also in London,Ont. Churchill Auditorium at the Technion is named after him.

At least five American high schools carry his name; these are located in Potomac, Maryland; Livonia, Michigan; Eugene, Oregon; East Brunswick, New Jersey and San Antonio, Texas.

Buildings, public squares and infrastructure

[edit]

![]() United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- The national and Commonwealth memorial to Churchill is Churchill College, Cambridge, which was founded in 1958 and opened in 1960. It is also home to the Churchill Archives Centre, which holds the papers of Sir Winston Churchill and over 570 collections of personal papers and archives documenting the history of the Churchill era and after.[44]

- In London, Churchill Place is one of the main squares in Canary Wharf.

- Also in London, The Churchill Arms was re-named after him after World War 2.[45]

- Energlyn and Churchill Park railway station in Wales is named in his honour.

- Churchill Square (Brighton and Hove), England

![]() USA:

USA:

- The Churchill occupying an entire block in New York City's Midtown Manhattan neighborhood is a residential building named after him, and features his portrait in the lobby and rooftop pool (rare for NYC residences).[46]

- In Fulton, Missouri, the National Churchill Museum.

![]() Canada:

Canada:

- The city of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada has a stop on the Edmonton LRT system and a public square named in his honour. Churchill Square, is the main square in that city and was renovated in 2004 for the city's 100th anniversary of incorporation.

- Churchill Square (St. John's), Newfoundland.

- The neighbourhood of Churchill Park, St. John's.

![]() France:

France:

- In Lyon, the Winston Churchill bridge.

- In Neuilly-sur-Seine, the Place Winston-Churchill.

![]() Czech Republic: Náměstí Winstona Churchilla (Winston Churchill Square) is located behind The Main Train Station in Prague, Czech Republic.

Czech Republic: Náměstí Winstona Churchilla (Winston Churchill Square) is located behind The Main Train Station in Prague, Czech Republic.

![]() Australia: The town of Churchill, Victoria.

Australia: The town of Churchill, Victoria.

![]() Belgium: A large dock in the Port of Antwerp was named after him by Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony in 1966.

Belgium: A large dock in the Port of Antwerp was named after him by Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony in 1966.

![]() The Netherlands: Churchillplein, a square in Rotterdam. Also the square in front of the World Forum in The Hague is named after him.

The Netherlands: Churchillplein, a square in Rotterdam. Also the square in front of the World Forum in The Hague is named after him.

![]() Fiji: Churchill Park (Lautoka) stadium.

Fiji: Churchill Park (Lautoka) stadium.

Other objects

[edit]

He appeared on the 1965 crown, the first commoner to be placed on a British coin.[47] He made another appearance on a crown issued in 2010 to honour the 70th anniversary of his Premiership.[48]

Pol Roger's prestige cuvée Champagne, Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill, is named after him. The first vintage, 1975, was launched in 1984 at Blenheim Palace. The name was accepted by his heirs as Churchill was a faithful customer of Pol Roger. Following Churchill's death in 1965, Pol Roger added a black border to the label on bottles shipped to the UK as a sign of mourning. This was not lifted until 1990.[49]

The Julieta (7" × 47), a size of cigar, is also commonly known as a Churchill.[citation needed]

Polls

[edit]Churchill has been included in numerous polls, mostly connected with greatness. Time named him its Man of the Year for 1940,[50] and "Man of the Half-Century" in 1949.[51] A BBC survey, of January 2000, saw Churchill voted the greatest British prime minister of the 20th century. In 2002, BBC TV viewers and web site users voted him the greatest Briton of all time in a ten-part series called Great Britons, a poll attracting almost two million votes.[52]

Statues

[edit]

Many statues have been created in likeness and in honour of Churchill. Numerous buildings and squares have also been named in his honour. The most prominent example of a statue of Churchill is the official statue commissioned by the government and created by Ivor Roberts-Jones which now stands in Parliament Square. It was unveiled by Churchill's widow, Lady Churchill, on 1 November 1973, and was Grade II listed in 2008.[53][54] In June 2020 when anti-racism protests occurred in the United Kingdom during the George Floyd protests, the statue of Sir Winston Churchill located in Parliament Square was vandalised when a protester painted graffiti on the statue reading “was a racist” underneath Churchill’s name which was crossed out by the same vandal who wrote the sentence. A couple of days after this event took place the statue was cleaned and it did not sustain any permanent damage.

Another Roberts-Jones statue of Churchill displaying the V sign[55] is prominently placed in New Orleans (erected in 1977).

In addition several other statues have also been made, including a bronze bust of Winston Churchill by Jacob Epstein (1947), several statues by David McFall at Woodford (1959), William McVey outside the British embassy in Washington, D.C. (1966), Franta Belsky at Fulton, Missouri (1969), at least three from Oscar Nemon: one on the front lawn of the Halifax Public Library branch on Spring Garden Road, Halifax, Nova Scotia (1980); one in the British House of Commons (1969); a bust of his head along with that of Franklin Roosevelt commemorating the Quebec Conference, 1943 next to Port St. Louis in Quebec City (1998); and one in Nathan Phillips Square outside of Toronto City Hall (1977), and Jean Cardot beside the Petit Palais in Paris (1998).[56] A statue of Churchill and Roosevelt, sculpted by Lawrence Holofcener is located in New Bond Street, London. There is an oversized bust of Churchill at the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site in Hyde Park, New York. It is paired with a similar bust of President Roosevelt.

After Churchill was declared the greatest Briton of all time in the BBC poll and television series Great Britons (see above), a statue was erected in his honour and now stands at the BBC television studios. Churchill is also memorialised by many statues and a public square in New York, in recognition of his life, and also because his mother was from New York. His maternal family is also memorialised in streets, parks, and neighbourhoods throughout the city.

In 2012, a statue of Churchill was erected in Jerusalem in recognition of his "staunch and unwavering support of the Jewish cause and their desire for a homeland".[57]

Orders, decorations and medals

[edit]This is a list of the orders, decorations, and medals received by Winston Churchill, arranged in order of precedence.

British orders and medals

[edit]-

Insignia of a Knight of the Order of the Garter

Order of the Garter (1953)[13]

Order of the Garter (1953)[13] Order of Merit[58] (1946)[13]

Order of Merit[58] (1946)[13] Order of the Companions of Honour (1922)[13]

Order of the Companions of Honour (1922)[13] The India Medal with clasp, Punjab Frontier 1897–98 (1898)[13]

The India Medal with clasp, Punjab Frontier 1897–98 (1898)[13] The Queen's Sudan Medal, 1896–98 (1899)[13]

The Queen's Sudan Medal, 1896–98 (1899)[13] The Queen's South Africa Medal, 1899–1902, with six clasps (1901)[13]

The Queen's South Africa Medal, 1899–1902, with six clasps (1901)[13] 1914-15 Star (1919)[13]

1914-15 Star (1919)[13] British War Medal 1914–1918 (1919)[13]

British War Medal 1914–1918 (1919)[13] Victory Medal (United Kingdom) 1914–1919 (1920)[13]

Victory Medal (United Kingdom) 1914–1919 (1920)[13] 1939–1945 Star (1945)[13]

1939–1945 Star (1945)[13] Africa Star (1945)[13]

Africa Star (1945)[13] Italy Star (1945)[13]

Italy Star (1945)[13] France and Germany Star (1945)[13]

France and Germany Star (1945)[13] Defence Medal (1945)[13]

Defence Medal (1945)[13] War Medal 1939–1945 (1945)[13]

War Medal 1939–1945 (1945)[13] King George V Coronation Medal (1911)[13]

King George V Coronation Medal (1911)[13] King George V Silver Jubilee Medal (1935)[13]

King George V Silver Jubilee Medal (1935)[13] King George VI Coronation Medal (1937)[13]

King George VI Coronation Medal (1937)[13] Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953)[13]

Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953)[13]Territorial Decoration (1924)[13]

Foreign honours

[edit]Orders

[edit]-

Collar of the Order of Leopold

-

Collar of the Order of Saint Olav

-

Collar of the Order of the Elephant

-

Star of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

Cross of the Order of Military Merit, Red Ribbon (War Service) (Spain, 1895)[13]

Cross of the Order of Military Merit, Red Ribbon (War Service) (Spain, 1895)[13]

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold with Palm (Belgium, 1945)[13]

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold with Palm (Belgium, 1945)[13] Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Netherlands Lion (Netherlands, 1946)[13]

Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Netherlands Lion (Netherlands, 1946)[13] Grand Cross, Order of the Oak Crown (Luxembourg, 1946)[13]

Grand Cross, Order of the Oak Crown (Luxembourg, 1946)[13] Grand Cross with Collar, Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav (Norway, 1948)[13]

Grand Cross with Collar, Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav (Norway, 1948)[13] Knight of the Order of the Elephant (Denmark, 1950)[13]

Knight of the Order of the Elephant (Denmark, 1950)[13] Companion of the Ordre de la Libération (France, 1958)[13]

Companion of the Ordre de la Libération (France, 1958)[13]Most Refulgent Order of the Star of Nepal, First Class (Nepal, 1961)[13]

Grand Sash of the High Order of Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi (Libya, 1962)[13]

Grand Sash of the High Order of Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi (Libya, 1962)[13] Order of the White Lion (Class I, civilian) (Czech Republic, posthumously 2014)[59][60]

Order of the White Lion (Class I, civilian) (Czech Republic, posthumously 2014)[59][60]

Decorations

[edit] Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army) (United States, 1919)[13]

Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army) (United States, 1919)[13] Cross of Liberty for Military Leadership, Grade I (Estonia, 1925)[13]

Cross of Liberty for Military Leadership, Grade I (Estonia, 1925)[13] Croix de Guerre with bronze Palm (Belgium, 1945)[13]

Croix de Guerre with bronze Palm (Belgium, 1945)[13] Military Medal (Luxembourg, 1946)[13][61]

Military Medal (Luxembourg, 1946)[13][61] Médaille militaire (France, 1947)[13][62]

Médaille militaire (France, 1947)[13][62] Croix de Guerre with bronze Palm (France, 1947)[13]

Croix de Guerre with bronze Palm (France, 1947)[13]

Service medals

[edit] Khedive's Sudan Medal (clasp: Khartoum) (Egypt, 1899)[13][63]

Khedive's Sudan Medal (clasp: Khartoum) (Egypt, 1899)[13][63] Cuban Volunteer Campaign Medal, 1895–98 (Spain, 1914)[64]

Cuban Volunteer Campaign Medal, 1895–98 (Spain, 1914)[64] King Christian X's Liberty Medal (Denmark, 1947)[13]

King Christian X's Liberty Medal (Denmark, 1947)[13]

Military ranks and titles

[edit]

- Cornet, 4th Queen's Own Hussars (20 February 1895)[65][66]

- Lieutenant, 4th Queen's Own Hussars (20 May 1896)[65][67] (resigned commission 3 May 1899)[68]

- Lieutenant, South African Light Horse (January 1900)[65]

- Captain, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars (QOOH), Imperial Yeomanry (4 January 1902)[65][69]

- Major, Henley Squadron, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars (27 May 1905)[65][70]

- Major, QOOH, attached to 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards (November 1915 – 5 January 1916)[65]

- Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary), QOOH, attached to 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers (5 January 1916 – March 1916)[65]

- Major, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars, Territorial Army (March 1916 – 1924)[65]

- Honorary Air Commodore of No. 615 Squadron RAF (4 Apr 1939 – 1957)[71]

- Honorary Colonel, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars (21 October 1939 – 13 October 1959)[72]

- Honorary Colonel, Royal Artillery, Territorial Army (21 October 1939 – 24 January 1965)[73]

- Honorary Colonel, 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers (24 January 1940 – 1947)[74]

- Colonel, 4th Queen's Own Hussars (22 October 1941 – 24 October 1958)[75]

- Honorary Colonel, 4th/5th (Cinque Ports) Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment (14 November 1941 – 24 January 1965)[76]

- Major, Territorial Army, Retired (20 February 1942)[73]

- Honorary Colonel, 489th (Cinque Ports) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA, Territorial Army (20 February 1942 – 1 July 1955)

- Honorary Colonel, 4th Battalion, The Essex Regiment (21 January 1945 – 24 January 1965)[77]

- Colonel, Queen's Royal Irish Hussars (24 October 1958 – 24 January 1965)[78]

- Honorary Pilot Wings, Royal Air Force (March 1943)

- Honorary Pilot Wings, United States Air Force[71]

- Colonel, Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels[71]

Academic

[edit]- Fellow of the Royal Society (1941–1965)[79]

- Rector of the University of Aberdeen (1914–18)[80]

- Rector of Edinburgh University (1929–32)[81]

- Chancellor of the University of Bristol (1929–1965)[82]

- Honorary Academician Extraordinary of the Royal Academy of Arts (1948–1965)[83]

- Honorary Professorship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1949)[84]

- Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium[85]

Honorary degrees

[edit]Churchill received many honorary doctorates from British universities as well other universities in the world, including:

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from Queen's University Belfast (Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK) in 1926[86][87]

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Rochester (Rochester, New York, US) on 16 June 1941[88][89]

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts, US) on 6 September 1943[86][90]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws (Hon. LL.D.) from McGill University (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) on 16 September 1944[91]

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Miami (Coral Gables, Florida, US) on 26 February 1946[92]

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Aberdeen (Aberdeen, Scotland, UK) on 27 April 1946[93]

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from Westminster College (Fulton, Missouri, US) on 5 May 1946[94]

- Doctorate honoris causa (Dr. h.c.) in Law from Leiden University (Leiden, Netherlands) on 10 May 1946[95]

- Honorary Doctor of Laws (Hon. LL.D.) from the University of London (London, England, UK) in 1948[96][97]

- Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Liverpool (Liverpool, England, UK) in 1949[98]

- Doctor Philosophiae Honoris Causa (Dr. Phil. h.c.) from the University of Copenhagen (Copenhagen, Denmark) in 1950[99]

Other distinctions

[edit]- Nobel Prize in Literature (1953)[100]

- Albert Gold Medal, Royal Society of Arts (1945)

- Companion of Literature, Royal Society of Literature (1961)[32]

- Grotius Medal, Netherlands (1949)

- Grand Seigneur of the Hudson's Bay Company (1955)[101]

- Karlspreis (1956)[102]

- The Williamsburg Award (7 December 1955)[103]

- Franklin Medal, City of Philadelphia, US (1956)

- 1st World Citizenship Award from Civitan International (1964)[citation needed]

- Theodor Herzl Award, Zionist Organization of America (1964)

- Honorary Bencher, Gray's Inn (18 February 1942)[104][105]

- Honorary Member, Lloyd's of London

- Honorary Life Member, Veteran's Fire Engine Company, Alexandria, Virginia (1960)

- Member of Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers

- President of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association 1959–1965[106]

Membership in lineage societies

[edit]- Royal Society of St George (Vice President)[citation needed]

- Society of the Cincinnati (1947)[107]

- Sons of the American Revolution (1963)[108]

Freedom of the City

[edit] 2 April 1941: Oldham[109]

2 April 1941: Oldham[109] 12 October 1942: Edinburgh[110]

12 October 1942: Edinburgh[110] 30 June 1943: London[111]

30 June 1943: London[111] 16 November 1944: Paris[112]

16 November 1944: Paris[112] 1945: Wanstead and Woodford[113]

1945: Wanstead and Woodford[113] 4 October 1946: Blackpool[114]

4 October 1946: Blackpool[114] 1946: Poole[115]

1946: Poole[115] 1946: Aberdeen

1946: Aberdeen 1946: Westminster[116]

1946: Westminster[116] 31 October 1946: Birmingham

31 October 1946: Birmingham 1947: Manchester[117][118]

1947: Manchester[117][118] 1947: Ayr[119]

1947: Ayr[119] 1947: Darlington[120]

1947: Darlington[120] 3 October 1947: Brighton[121][122]

3 October 1947: Brighton[121][122] 22 April 1948: Eastbourne[123][124]

22 April 1948: Eastbourne[123][124] 6 July 1948: Aldershot[125]

6 July 1948: Aldershot[125] 16 July 1948: Cardiff[126][127]

16 July 1948: Cardiff[126][127] 27 May 1948: Perth[128]

27 May 1948: Perth[128] 1949: Kensington[129][130]

1949: Kensington[129][130] 20 May 1950: Worcester[131]

20 May 1950: Worcester[131] 13 July 1950: Bath[132]

13 July 1950: Bath[132] 12 December 1950: Portsmouth[133]

12 December 1950: Portsmouth[133] 2 March 1951: Swindon[134]

2 March 1951: Swindon[134] 16 April 1951: Sheffield[135][136][137]

16 April 1951: Sheffield[135][136][137] 15 August 1951: Deal[138][139]

15 August 1951: Deal[138][139] 1951: Aberystwyth[140]

1951: Aberystwyth[140] 1951: Dover[141]

1951: Dover[141] 1953: Stirling

1953: Stirling 17 January 1953: Kingston[142][143]

17 January 1953: Kingston[142][143] 15 December 1950: Portsmouth[144][145]

15 December 1950: Portsmouth[144][145] 30 September 1955: Harrow[146]

30 September 1955: Harrow[146] 16 December 1955: Derry[147]

16 December 1955: Derry[147] 16 December 1955: Belfast[148][149][101][150]

16 December 1955: Belfast[148][149][101][150] 3 March 1956: Roquebrune-Cap-Martin[151][152]

3 March 1956: Roquebrune-Cap-Martin[151][152] 23 July 1957: Douglas[153]

23 July 1957: Douglas[153] 27 November 1957: Margate

27 November 1957: Margate 28 October 1958: Leeds

28 October 1958: Leeds 10 October 1964: Estcourt[154]

10 October 1964: Estcourt[154]

Churchill received a worldwide total of 42 Freedoms of Cities and Towns in his lifetime, a record for a lifelong British citizen.[155]

Sources

[edit]- ^ Picknett, et al., p. 252.

- ^ "Winston Churchill's History-Making Funeral". 3 September 2018.

- ^ Gould, Peter (8 April 2005). "Europe | Holding history's largest funeral". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "The Life of Churchill". 18 June 2008.

- ^ a b c Paul Courtenay, The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill. Archived 18 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 20 July 2013).

- ^ "No. 17256". The London Gazette. 3 June 1817. p. 1277.

- ^ Robson, Thomas, The British Herald, or Cabinet of Armorial Bearings of the Nobility & Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, Volume I, Turner & Marwood, Sunderland, 1830, p. 401 (CHU-CLA).

- ^ Plumpton, John (Summer 1988). "A Son of America Though a Subject of Britain". Finest Hour (60).

- ^ HelmerReenberg (29 May 2013). "April 9, 1963 – President John F. Kennedy declares Winston Churchill an honorary citizen of the USA". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (6 April 2015). Winston S. Churchill: Road to Victory, 1941–1945. Rosetta Books. ISBN 9780795344664.

- ^ Rintala, Marvin (1985). "Renamed Roses: Lloyd George, Churchill, and the House of Lords" (pdf). Biography. 8 (3). University of Hawai'i Press: 248–264. doi:10.1353/bio.2010.0448. ISSN 0162-4962. JSTOR 23539091. S2CID 159908334. Retrieved 24 January 2023 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (1981). Their Noble Lordships : The hereditary peerage today. London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber. p. 72. ISBN 0-571-11069-X – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an The Orders, Decorations and Medals of Sir Winston Churchill by Douglas Russell

- ^ Ramsden, John (2002). Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and His Legend Since 1945. Columbia University Press. pp. 113, 597. ISBN 9780231131063.

- ^ "Welcome to WinstonChurchill.org". Archived from the original on 7 February 2007.

- ^ a b "Sir Winston Churchill: A chronology". Churchill Archives Centre. Churchill College, University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "No. 35326". The London Gazette. 28 October 1941. p. 6247.

- ^ "Privy Council Office – Bureau du Conseil privé". Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Fedden, Robin (15 May 2014). Churchill at Chartwell: Museums and Libraries Series. Elsevier. ISBN 9781483161365.

- ^ "Questions Answered: Winston Churchill in uniform and Ralph or Rafe". The Times. 13 September 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ "No. 41083". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 May 1957. p. 3227.

- ^ "THE QUEEN'S OWN OXFORDSHIRE HUSSARS AND BLENHEIM". International Churchill Society. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars". Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Winston Churchill—A Painter at Marrakech". Classic Chicago Magazine. 4 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Record from The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901–1956". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ "The Society of the Cincinnati". Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Sir Winston Churchill (1874 - 1965)". Royal Academy. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "Winston Churchill- Deputy Lieutenant". America's National Churchill Museum. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Literature 1953". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Winston Churchill hero file". AU: More or Less. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen – Detail". DE: Karlspreis. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Companions of Literature". Royal Society of Literature. 2 September 2023.

- ^ CIOB

- ^ Armbrester, Margaret E. (1992). The Civitan Story. Birmingham, AL: Ebsco Media. pp. 96–97.

- ^ "Colonels web site". Kycolonels.org. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Kentucky: Secretary of State – Kentucky Colonels". Sos.ky.gov. 26 October 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "The Teeth That Saved The World? — The Royal College of Surgeons of England". 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007.

- ^ "Home – USS W.S. Churchill". Churchill.navy.mil. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Chris Shillito. "The Churchill Tank". Armourinfocus.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Sale threatens future of Churchill Arms". Ottawa Citizen. 1 April 1986. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ René Dings (30 August 2016). "Naar welke personen zijn de meeste straten genoemd?". René Dings. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Greenland, James (24 August 2012). "Crofton Downs' stately links to Britain". The Wellingtonian. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Norway Rd (1 January 1970). "Churchill NOrway – Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Churchill College : Churchill Archives Centre". Chu.cam.ac.uk. 6 March 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "5 Things You Probably Didn't Know About The Churchill Arms". Londonist. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

Of course, the pub wasn't named after him, anyway, until after the end of the second world war.

- ^ "The Churchill at 300 East 40th St. In Murray Hill".

- ^ "1965 Churchill Crown". 24carat.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Winston Churchill £5 Crown from the British Royal Mint". CoinUpdate.com. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Pol Roger UK: Sir Winston Churchill Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12 July 2010

- ^ "GREAT BRITAIN: Man of the Year". Time. 6 January 1941. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ "Winston Churchill, Man of the Year". Time. 2 January 1950. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ BBC – Great Britons.

- ^ Sherna Noah (1 January 2004). "Churchill statue 'had the look of Mussolini'". The Independent. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ "Sir Winston Churchill". Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ "Winston Churchill - New Orleans, LA - Statues of Historic Figures on Waymarking.com".

- ^ "Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer (1874–1965), prime minister – Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32413. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Stewart, Catrina (3 November 2012). "Sir Winston Churchill: Zionist hero". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "THE STATE FUNERAL OF SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL (NEWS IN COLOUR) - COLOUR IS VERY GOOD". British Movietone News. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2024 – via Youtube.

- ^ ČTK. "Seznam osobností vyznamenaných letos při příležitosti 28. října". ceskenoviny.cz. (in Czech)

- ^ "White Lion goes to Winton and Winston". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016.It was conferred on same occasion as the same award was given to Sir Nicholas Winton.

- ^ "Luxembourg's WW2 Medals". Users.skynet.be. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ (Although some references report Churchill was awarded the French Legion of Honour, it is not listed among his honours at the Churchill Centre. However, it is significant that Churchill received the Médaille militaire, which is only awarded (for high leadership) to holders of the Legion's Grand Cross). The Listing of Foreign recipients of the Legion of Honour reports Churchill as "Sir Winston Churchill, Grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur (1958);" (The Grand-croix being awarded to Foreign Heads of state).

- ^ "Khedive's Sudan Medal 1896–1908".

- ^ Cuban Campaign Volunteer Medal 1895-1898

- ^ a b c d e f g h Olsen, John (17 October 2008). "Churchill's Commissions and Military Attachments". Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "No. 26600". The London Gazette. 19 February 1895. p. 1001.

- ^ "No. 26751". The London Gazette. 23 June 1896. p. 3642.

- ^ "No. 27076". The London Gazette. 2 May 1899. p. 2806.

- ^ "No. 27393". The London Gazette. 3 January 1902. p. 10.

- ^ "No. 27799". The London Gazette. 30 May 1905. p. 3866.

- ^ a b c Who Was Who, 1961–1970. p. 206.

- ^ "Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 474.

- ^ The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 925.

- ^ The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 317.

- ^ The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 1067.

- ^ "4th Battalion, the Essex Regiment [UK]". www.regiments.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "4th Queen's Own Hussars". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "Winston Churchill- Fellow of the Royal Society". National Churchill Museum.

- ^ "Aberdeen academic explores Churchill's leadership success and his links to Scotland". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "The Rector". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Bristol University – News – 2004: Chancellor".

- ^ "Sir Winston Churchill – Artist – Royal Academy of Arts". royalacademy.org.uk.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie named honorary visiting professor". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. December 1993. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Index biographique des membres et associés de l'Académie royale de Belgique (1769–2005). p. 55

- ^ a b "Brothers in Arms: Winston Churchill Receives Honorary Degree – Harvard Library". library.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ “1926, Belfast” (BRDW 1/2/107) – website Churchill pictures

- ^ "Commencement history: Winston Churchill addresses Class of 1941 by radio". 11 May 2016.

- ^ Office of the Provost: Honorary Degree Recipients 1940–1949 – website of the University of Rochester

- ^ Honorary Degrees – website of Harvard University

- ^ "XYZ". Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Alumni Digest: Winston Churchill, UM Class of 1946 – website of the University of Miami Magazine

- ^ Winston Churchill visits Aberdeen – moving image archive website of the National Library of Scotland

- ^ "National Churchill Museum – Blog". nationalchurchillmuseum.org.

- ^ "How Sir Winston Churchill became a Leiden Honorary Doctor". Leiden University. 9 May 2016.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "London Varsity Honours Churchill (1948)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Degree (1948)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Honorary Graduates of the University Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine – website of the University of Liverpool

- ^ Aeresdoktorer – website of the University of Copenhagen

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1953". The Nobel Prize. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ a b British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Presentation To Winston Churchill At Beaver Hall (1956)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Aachen Honours Churchill (1956)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Colonial Williamsburg (30 March 2011). "Presentation of the Williamsburg Award (Churchill Bell Award) to Sir Winston Churchill". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Historical List of Honorary Benchers since 1883" (PDF). Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Prime Ministers & the Inns of Court" (PDF). Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Association, Victoria Cross and George Cross. "The VC and GC Association". vcgca.org.

- ^ "The Society of the Cincinnati". societyofthecincinnati.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ "Our Mission". National Society Sons of the American Revolution. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Oldham Council. "Honorary Freemen of the Borough".

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Premier In Scotland Aka Churchill In Scotland (1942)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill A Freeman Aka Churchill Made A Freeman Of London (1943)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "CHURCHILL RECEIVES FREEDOM OF PARIS - SOUND | AP Archive".

- ^ "Autumn 1945 (Age 70) – The International Churchill Society". 20 March 2015.

- ^ "When Blackpool Gave Freedom of the Borough to Winston Churchill – Blackpool Winter Gardens Trust". wintergardenstrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "When Sir Winston Churchill received special honour from Poole". Bournemouth Echo. 28 January 2015.

- ^ British Movietone (21 July 2015). "CHURCHILL RECEIVES FREEDOM OF WESTMINSTER". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Pathé. "Churchill: Freedom Of Manchester".

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Receives Freedom Of Manchester (1947)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Winston Churchill Receives Freedom Of Ayr Aka Pathe Front Page (1947)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Ramsden, John (2002). Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and His Legend Since 1945. Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780231131063.

- ^ "Freedom of the Borough – Corporation and Council – Topics – My Brighton and Hove". Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Receives Freedom Of Brighton (1947)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Mr Winston Churchill seen receiving the Freedom of Eastbourne, Sussex from Councillor Randolph E as a 22"x18" (58x48cm) Framed Print". Media Storehouse. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Reno Gazette-Journal, 22 April 1948, p. 14

- ^ "Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill".

- ^ "HONORARY FREEMAN OF THE CITY AND COUNTY OF CARDIFF" (PDF). Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Gets Freedom Of Cardiff (1948)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Full record for 'CHURCHILL RECEIVES THE FREEDOM OF PERTH' (0841) – Moving Image Archive catalogue".

- ^ "Appointment of Honorary Persons". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Receives Freedom Of Kensington (1949)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Selected Originals – Churchill Receives Freedom Of Worcester (1950)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Telegraph-Herald – Google News Archive Search".

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "'pompey's' New Freeman (1950)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "On this day from Monday, February 27 2017". Swindon Advertiser. 27 February 2017.

- ^ "Picture Sheffield".

- ^ "Retro: Sheffield honours Churchill with freedom of city".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Retro: Sheffield honours Churchill with freedom of city". thestar.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Selected Originals – Two Freedoms For Churchill (1951)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Eliot Crawshay-Williams – Program Signed 08/15/1951 – Autographs & Manuscripts – HistoryForSale Item 52843". HistoryForSale Autographs & Manuscripts.

- ^ Talat Chaudhri. "Honorary Freemen".

- ^ "Dover's Home Guard". 16 April 2016.

- ^ "City Schedules Churchill Fete". The Windsor Daily Star. 17 January 1953. p. 13.

- ^ "Churchill Visits Jamaica". Colonial Film. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "Churchill is awarded The Freedom of Portsmouth".

- ^ "Freedom of the city & keys of the city". Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Freedoms granted by Harrow". Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "Freedom of city was last granted in 1963". The Irish Times. 2 May 2000.

- ^ "The Glasgow Herald – Google News Archive Search".

- ^ "SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL RECEIVES FREEDOM OF THE CITY OF BELFAST & LONDONDERRY". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Selected Originals – Ulster Honours Churchill Aka Ulster Honours Sir Winston Aka Churchill 2 (1955)". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ British Movietone (21 July 2015). "SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL – HONORARY CITIZEN". Archived from the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Emery and Wendy Reves "La Pausa" Goes on Sale - the International Churchill Society". Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "Douglas Borough Council – Freedom of the Borough of Douglas". douglas.gov.im.

- ^ Sandys, Celia (2014). Chasing Churchill: The Travels of Winston Churchill. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 9781910065297.

- ^ McWhirter, Ross and Norris (1972). The Guinness Book of Records. Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 184. ISBN 0900424060.At the time of publication the world record was the 57 conferred on Andrew Carnegie who was born in Scotland but emigrated in 1848, subsequently becoming a US citizen.